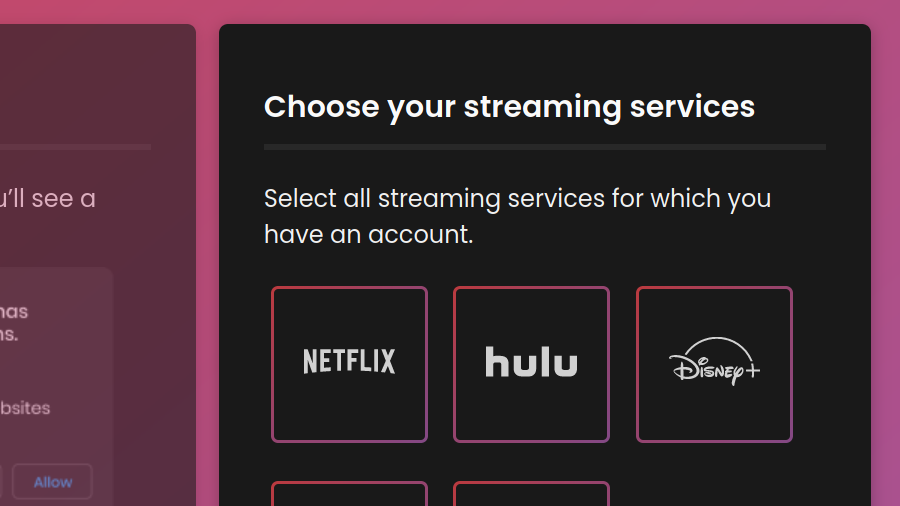

Teleparty, formerly called Netflix Party, is a wildly popular browser extension with at least 10 million users on Google Chrome (likely much more as with Chrome Web Store anything beyond 10 million is displayed as “10,000,000+”) and 1 million users on Microsoft Edge. It lets people from different location join a video viewing session, watching a movie together and also chatting while at it. A really nifty extension actually, particularly in times of a pandemic.

While this extension’s functionality shouldn’t normally be prone to security vulnerabilities, I realized that websites could inject arbitrary code into its content scripts, largely thanks to using an outdated version of the jQuery library. Luckily, the internal messaging of this extension didn’t allow for much mischief. I found some additional minor security issues in the extension as well.

Contents

The thing with jQuery

My expectation with an extension like Teleparty would be: worst-case scenario is opening up vulnerabilities in websites that the extension interacts with, exposing these websites to attacks. That changed when I realized that the extension used jQuery 2.1.4 to render its user interface. This turned all of the extension into potentially accessible attack surface.

When jQuery processes HTML code, it goes beyond what Element.innerHTML does. The latter essentially ignores <script> tags, the code contained there doesn’t execute. To compensate for that, jQuery extracts the code from <script> tags and passes it to jQuery.globalEval(). And while in current jQuery versions jQuery.globalEval() will create an inline script in the document, in older versions like jQuery 2.1.4 it’s merely an alias for the usual eval() function.

And that makes a huge difference. The Content Security Policy of the Teleparty extension pages didn’t allow inline scripts, yet it contained 'unsafe-eval' keyword for some reason, so eval() calls would be allowed. And while this Content Security Policy doesn’t apply to content scripts, inline scripts created by content scripts execute in page context – yet eval() calls execute code in the context of the content script itself.

Finding an HTML injection point

Now Teleparty developers clearly aren’t clueless about the dangers of working with jQuery. It’s visible that they largely avoided passing dynamic data to jQuery. In cases where they still did it, they mostly used safe function calls. Only a few places in the extension actually produce HTML code dynamically, and the developers took considerable care to escape HTML entities in any potentially dangerous data.

They almost succeeded. I couldn’t find any exploitable issues with the extension pages. And the content scripts only turned out exploitable because of another non-obvious jQuery feature that the developers probably weren’t even aware of. The problem was the way the content scripts added messages to the chat next to the viewed video:

getMessageElementWithNickname(userIconUrl, userNickname, message)

{

return jQuery(`

<div class="msg-container">

<div class="icon-name">

<div class="icon">

<img src="${escapeStr(userIconUrl)}">

</div>

</div>

<div class="msg-txt message${message.isSystemMessage ? "-system" : "-txt"}">

<h3>${userNickname}</h3>

<p>${message.body}</p>

</div>

</div>

`);

}

You can see that HTML entities are explicitly escaped for the user icon but not the nickname or message body. These are escaped by the caller of this function however:

addMessage(message, checkIcons) {

...

const userIcon = this.getUserIconURL(message.permId, message.userIcon)

const userNickname = this.getUserNickname(message.permId, message.userNickname);

message.body = escapeStr(message.body);

const messageElement =

this.getMessageElementWithNickname(userIcon, userNickname, message);

this._addMessageToHistory(messageElement, message, userIcon, userNickname);

...

}

Actually, for the nickname you’d have to look into the getUserNickname() method but it does in fact escape HTML entities. So it’s all safe here. Except that there is another caller, method _refreshMsgContainer() that is called to update existing messages whenever a user changed their name:

_refreshMsgContainer(msgContainer) {

const permId = msgContainer.data("permId");

...

const userNickname = this.getUserNickname(permId);

if (userNickname !== msgContainer.data("userNickname"))

{

const message = msgContainer.data("message"),

userIcon = this.getUserIconURL(permId),

nicknameMessage =

this.getMessageElementWithNickname(userIcon, userNickname, message);

msgContainer.replaceWith(nicknameMessage);

...

}

}

Note how jQuery.data() is used to retrieve the nickname and message associated with this element. This data was previously attached by _addMessageToHistory() method after HTML entities have been escaped. No way for the website to mess with this data either as it is stored in the content script’s “isolated world.”

Except, if jQuery.data() doesn’t find any data attached there is a convenient fallback. What does it fall back to? HTML attributes of course! So a malicious website merely needs to produce its own fake message with the right attributes. And make sure Teleparty tries to refresh that message:

<div class="msg"

data-perm-id="rand"

data-user-nickname="hi"

data-message='{"body":"<script>alert(chrome.runtime.id)</script>"}'

data-user-icon="any.svg">

</div>

Note that jQuery will parse JSON data from these attributes. That’s very convenient as the only value usable to inject malicious data is message, and it needs a message.body property.

Making sure the payload fires

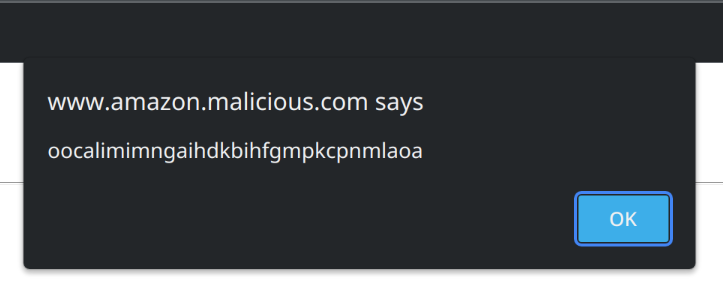

Now it isn’t that easy to make Teleparty call _refreshMsgContainer() on our malicious message. There has to be an active Teleparty session on the page first. Luckily, Teleparty isn’t very picky as to what websites are considered streaming sites. For example, any website with .amazon. in the host name and a <video> tag inside a container with a particular class name is considered Amazon Prime Video. Easy, we can run this attack from www.amazon.malicious.com!

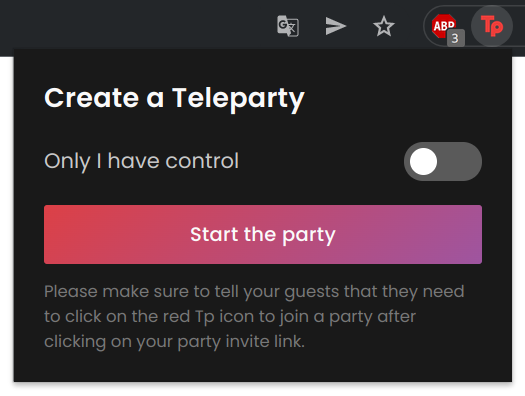

Still, a Teleparty session is required. So a malicious website could trick the user into clicking the extension icon and starting a session in the pop-up.

Probably doable with a little social engineering. But why ask users to start a session, potentially rendering them suspicious, when we can have them join an existing session? For that they need to go to https://redirect.teleparty.com/join/0123456789abcdef where 0123456789abcdef is the session identifier and click the “Join the Party” button. This website has no HTTP headers to prevent being loaded in a frame, seems to be a perfect target for a Clickjacking attack.

Except that there is a bug in the way the extension integrates with this page, and the communication fails if it isn’t the top-level document. No, this clearly isn’t intentional, but it means no clickjacking for you. But rather:

- The malicious website creates a Teleparty session (requires communicating via WebSockets, no big deal).

- It then opens

https://redirect.teleparty.com/join/0123456789abcdefwith the correct session ID, asking the user to join (social engineering after all). - If the user clicks “Join the Party,” they will be redirected back to the malicious page.

- Teleparty initiates a session: Boom.

One point here needs additional clarification: the malicious website isn’t Amazon Prime Video, so how come Teleparty redirected to it? That’s actually an Open Redirect vulnerability. With Amazon (unlike the other streaming services) having 21 different domains, Teleparty developers decided to pass a serviceDomain parameter during session creation. And with this parameter not being checked at all, a malicious session could redirect the user anywhere.

The impact

While the background page of the Teleparty extension usually has access to all websites, its content scripts do not. In addition to being able to access their webpage (which the attackers control anyway) they can only access content script data (meaning only tab ID here) and use the extension’s internal messaging. In case of Teleparty, the internal messaging mostly allows messing with chats which isn’t too exciting.

The only message which seems to have significant impact is reInject. Its purpose is injecting content scripts into a given tab, and it will essentially call chrome.tabs.executeScript() with the script URL from the message. And this would have been pretty bad if not for an additional security mechanism implemented by the browsers: only URLs pointing to files from the extension are allowed.

And so the impact here is limited to things like attempting to create Teleparty sessions for all open tabs, in the hopes that the responses will reveal some sensitive data about the user.

Additional issues

Teleparty earns money by displaying ads that it receives from Kevel a.k.a. adzerk.net. Each advertisement has a URL associated with it that will be navigated to on click. Teleparty doesn’t perform any validation here, meaning that javascript: URLs are allowed. So a malicious ad could run JavaScript code in the context of the page that Teleparty runs in, such as Netflix.

It’s also generally a suboptimal design solution that the Teleparty chat is injected directly into the webpage rather than being isolated in an extension frame. This means that your streaming service can see the name you are using in the chat or even change it. They could also read out all the messages you exchange with your friends or send their own in your name. But we all trust Netflix, don’t we?

The fix

After I reported the issue, Teleparty quickly changed their server-side implementation to allow only actual Amazon domains as serviceDomain, thus resolving the Open Redirect vulnerability. Also, in Teleparty 3.2.5 the use of jQuery.data() was replaced by usual expando properties, fixing the code injection issue. As an additional precaution, 'unsafe-eval' was removed from the extension’s Content Security Policy.

At the time of writing, Teleparty still uses the outdated jQuery 2.1.4 library. The issues listed under Additional issues haven’t been addressed either.

Timeline

- 2022-01-24: Reported vulnerability via email.

- 2022-01-25: Reached out to a staff member via Discord server: the email got sorted into spam as I suspected.

- 2022-01-26: Received a response via email stating that the Open Redirect vulnerability is resolved and a new extension version is about to be released.

Comments