Everyone has received the mails trying to extort money by claiming to have hacked a person’s webcam and recorded a video of them watching porn. These are a bluff of course, but the popular Screencastify browser extension actually provides all the infrastructure necessary for someone to pull this off. A website that a user visited could trick the extension into starting a webcam recording among other things, without any indications other than the webcam’s LED lighting up if present. The website could then steal the video from the user’s Google Drive account that it was uploaded to, along with anything else that account might hold.

Screencastify is a browser extension that aids you in creating a video recording of your entire screen or a single window, optionally along with your webcam stream where you explain what you are doing right now. Chrome Web Store shows “10,000,000+ users” for it which is the highest number it will display – same is shown for extensions with more than 100 million users. The extension is being marketed for educational purposes and gained significant traction in the current pandemic.

As of now, it appears that Screencastify only managed to address the Cross-site Scripting vulnerability which gave arbitrary websites access to the extension’s functionality, as opposed to “merely” Screencastify themselves and a dozen other vendors they work with. As this certainly won’t be their last Cross-site Scripting vulnerability, I sincerely recommend staying clear of this browser extension.

Update (2022-05-25): Version 2.70.0.4517 of the extension released today restricted the attack surface considerably. Now it’s only five subdomains, run by Screencastify and one other vendor. Update (2022-05-31): Screencastify reduced the attack surface further by no longer granting websites access to the user’s Google Drive. And as of version 2.70.1.4520 all five subdomains with privileged access to the extension are run by Screencastify themselves. As far as I can tell, with these changes the issue can no longer be exploited.

Contents

Website integration

Screencastify extension integrates with its website. That’s necessary for video editing functionality which isn’t part of the extension. It’s also being used for challenges: someone creates a challenge, and other people visit the corresponding link, solving it and submitting their video. To enable this integration the extension’s manifest contains the following:

"externally_connectable": {

"matches": [

"https://*.screencastify.com/*"

]

},

So any page on the screencastify.com domain can send messages to the extension. What kind of messages? Lots of them actually. For example:

case 'bg:getSignInToken':

// sends token for success and false for failure

asyncAction = this._castifyAuth.getAuthToken({ interactive: true });

break;

Let’s see what happens if we open Developer Tools somewhere on screencastify.com and run the following:

chrome.runtime.sendMessage("mmeijimgabbpbgpdklnllpncmdofkcpn", {

type: "bg:getSignInToken"

}, response => console.log(response));

This indeed produces an authentication token, one that starts with ya29.. And a quick search shows that this is the format of Google’s OAuth access token. It indeed belongs to the account that the Screencastify extension has been configured with (extension isn’t usable without), granting full read/write privileges for Google Drive.

Side note: There is a reason why Screencastify has to request full access to Google Drive, and it is a design flaw on Google’s end. An app can request access to an app-specific folder which would be sufficient here. But unlike Dropbox for example, Google Drive hides app-specific folders from the user. And users not being able to see their own uploaded videos is quite a showstopper. So Screencastify has to request full access, create a user-visible folder and upload videos there.

Another piece of functionality allows websites to establish a connection to the extension. Once it has the connection port, the website can send e.g. the following message through it:

port.postMessage({type: "start", data: {captureSource: "desktop"}});

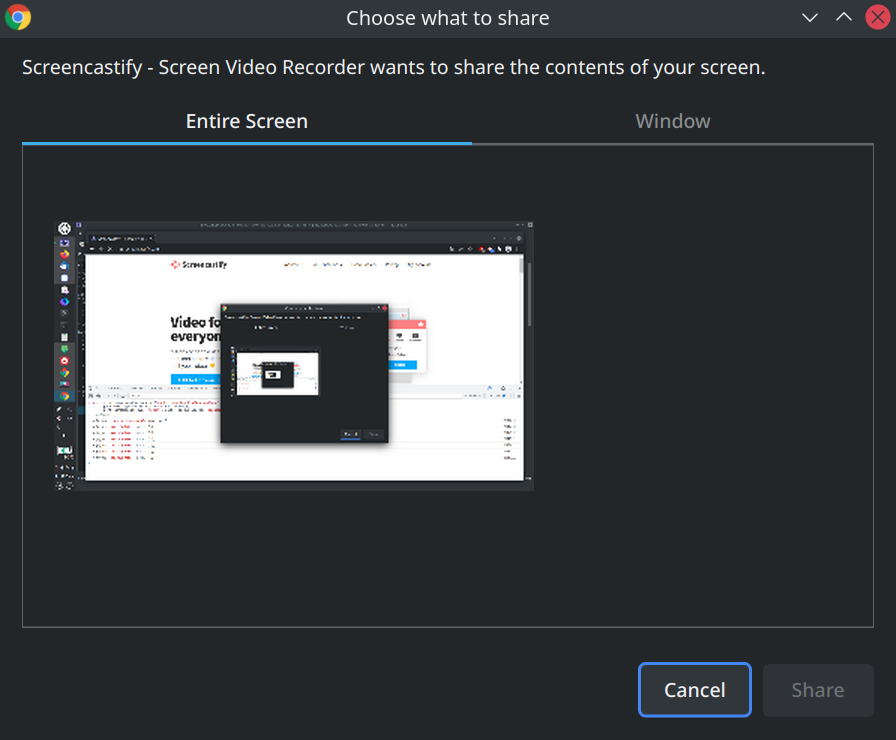

This will bring up the following dialog window:

That’s Chrome’s desktopCapture API in action. If this dialog is accepted, recording will start. So the user needs to cooperate.

There are other possible values for captureSource, for example "tab". It will attempt to use tabCapture API and fails because this API can only be used in response to a direct user action (no idea why Chrome is stricter here than with screen recordings).

And there is "webcam". This uses the same WebRTC API that is available to web pages as well. The difference when using it from a browser extension: the user only needs to grant the permission to access the webcam once. And Screencastify requests that permission as part of its onboarding. So starting a webcam recording session usually happens without requiring any user interaction and without any visual indicators. Later the recording can be stopped:

port.postMessage({type: "stop", data: false});

And with the default settings, the recorded video will be automatically uploaded to Google Drive. As we remember, the website can get the access token necessary to download it from there.

Who controls screencastify.com?

Let’s sum up: the extension grants screencastify.com enough privileges to record a video via user’s webcam and get the result. No user interaction is required, and there are only minimal visual indicators of what’s going on. It’s even possible to cover your tracks: remove the video from Google Drive and use another message to close the extension tab opened after the recording. That’s considerable power. Who could potentially abuse it?

Obviously, there is Screencastify itself, running app.screencastify.com and a bunch of related subdomains. So the company itself or a rogue employee could plant malicious code here. But that’s not the end of it. The entities controlling subdomains of screencastify.com (not counting hosting companies) are at the very least:

- Webflow, running www.screencastify.com

- Teachable, running course.screencastify.com

- Atlassian, running status.screencastify.com

- Netlify, running quote.screencastify.com

- Marketo, running go.screencastify.com

- ZenDesk, running learn.screencastify.com

That’s quite a few companies users are expected to trust.

And who else?

So it’s a domain running quite a few web applications from different companies, all with very different approaches to security. One thing they have in common however: none of the subdomains seem to have meaningful protection in terms of Content Security Policy. With such a large attack surface, exploitable Cross-site Scripting (XSS) vulnerabilities are to be expected. And these would give anyone the power to attack Screencastify users.

In order to make a point I decided to locate an XSS vulnerability myself. The Screencastify web app is written with the Angular framework which is not up my alley. Angular isn’t usually prone to XSS vulnerabilities, and the Screencastify app doesn’t do anything out of the ordinary. Still, I managed to locate one issue.

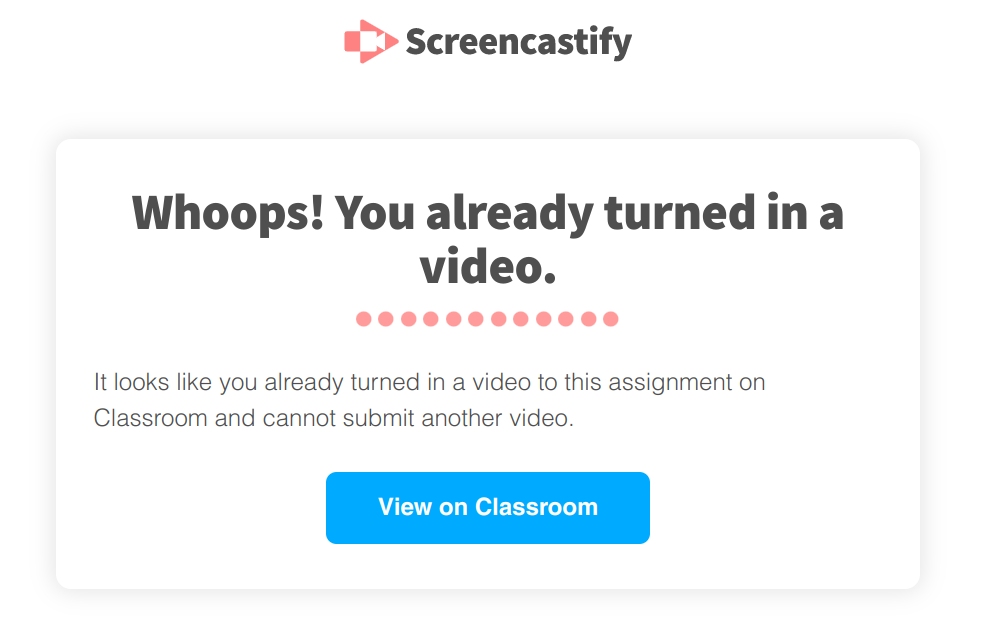

The problem was located in the error page displayed if you already submitted a video to a challenge and were trying to submit another one. This error page is located under a fixed address, so it can be opened directly rather than triggering the error condition:

The interesting part here is the “View on Classroom” button meant to send you to Google Classroom. What does clicking this button do?

window.open(this.courseworkLink);

Where does this.courseworkLink come from? It’s a query string parameter. Is there some link validation in between? Nope. So, if the query string parameter is something like javascript:alert(document.domain), will clicking this button run JavaScript code in the context of the screencastify.com domain? It sure will!

The attackers would still need to trick the user into actually clicking this button of course. But without any framing protection, this page is susceptible to Clickjacking attacks. So my proof-of-concept page loaded the vulnerable page in an invisible frame and positioned it under the mouse cursor in such a way that any click would go to the “View on Classroom” button. Once the user clicked the page could message Screencastify, retrieve the Google access token from it and ask Google for user’s identity. Reading out Google Drive contents or starting a recording session would have been possible as well.

The (lack of a) fix

I reported the issues to Screencastify on February 14, 2022. I received a response on the very same day, and a day later came the confirmation about the XSS vulnerability being resolved. The mail also mentioned that adding a Content Security Policy would be their long-term plan, but as of now this hasn’t happened on either app.screencastify.com or www.screencastify.com beyond framing protection.

Looking at the most current Screencastify 2.69.0.4425 release, the externally_connectable manifest entry still allows all of screencastify.com to connect to the extension. In fact, there is now even a second entry: with app.pendo.io one more vendor was added to the mix of those who could already potentially exploit this extension.

Was the API accessible this way restricted at least? Doesn’t look like it. This API will still readily produce the Google OAuth token that can be used to access your Google Drive. And the onConnectExternal handler allowing websites to start video recording is still there as well. Not much appears to have changed here and I could verify that it is still possible to start a webcam recording without any visual clues.

So, the question whether to keep using Screencastify at this point boils down to whether you trust Screencastify, Pendo, Webflow, Teachable, Atlassian, Netlify, Marketo and ZenDesk with access to your webcam and your Google Drive data. And whether you trust all of these parties to keep their web properties free of XSS vulnerabilities. If not, you should uninstall Screencastify ASAP.

Update (2022-05-25): Screencastify released version 2.70.0.4517 of their extension today. This release finally restricts the externally_connectable manifest entry, now it says:

"externally_connectable": {

"matches": [

"https://captions.screencastify.com/*",

"https://edit.screencastify.com/*",

"https://questions.screencastify.com/*",

"https://watch.screencastify.com/*",

"https://www.screencastify.com/*"

]

},

While this still includes www.screencastify.com which is run by Webflow, this is much better than before and limits the attack surface considerably.

Update (2022-05-31): A further look into version 2.70.0.4517 shows that bg:getSignInToken endpoint has been removed, this further defuses the issue here. Also, version 2.70.1.4520 released on May 27 changes the list of the sites allowed to connect once again, replacing www.screencastify.com by app.screencastify.com. So now all domains granted this access are indeed run by Screencastify and not by third parties.

Comments

Hi, very interesting article, thanks! I've one question, if you could answer: How did you find out the entities controlling the subdomains of screencastify.com? Am I right if I say that only owners of 2nd-level domains can issue certificates for 3rd level? Thanks

In most cases it’s already visible in the DNS records:

Some subdomains are hosted on AWS which isn’t as obvious. Page content and source usually indicate who they belong to. And you can check out the vendor to see whether they offer managed services / who they are hosting with.

As to who can issue certificates: no, with Let’s Encrypt for example anybody controlling a subdomain can get an SSL certificate for this subdomain directly. They don’t need to prove domain ownership.