As we’ve seen in the previous article, a browser extension isn’t very different from a website. It’s all the same HTML pages and JavaScript code. The code executes in the browser’s regular sandbox. So what can websites possibly gain by exploiting vulnerabilities in a browser extension?

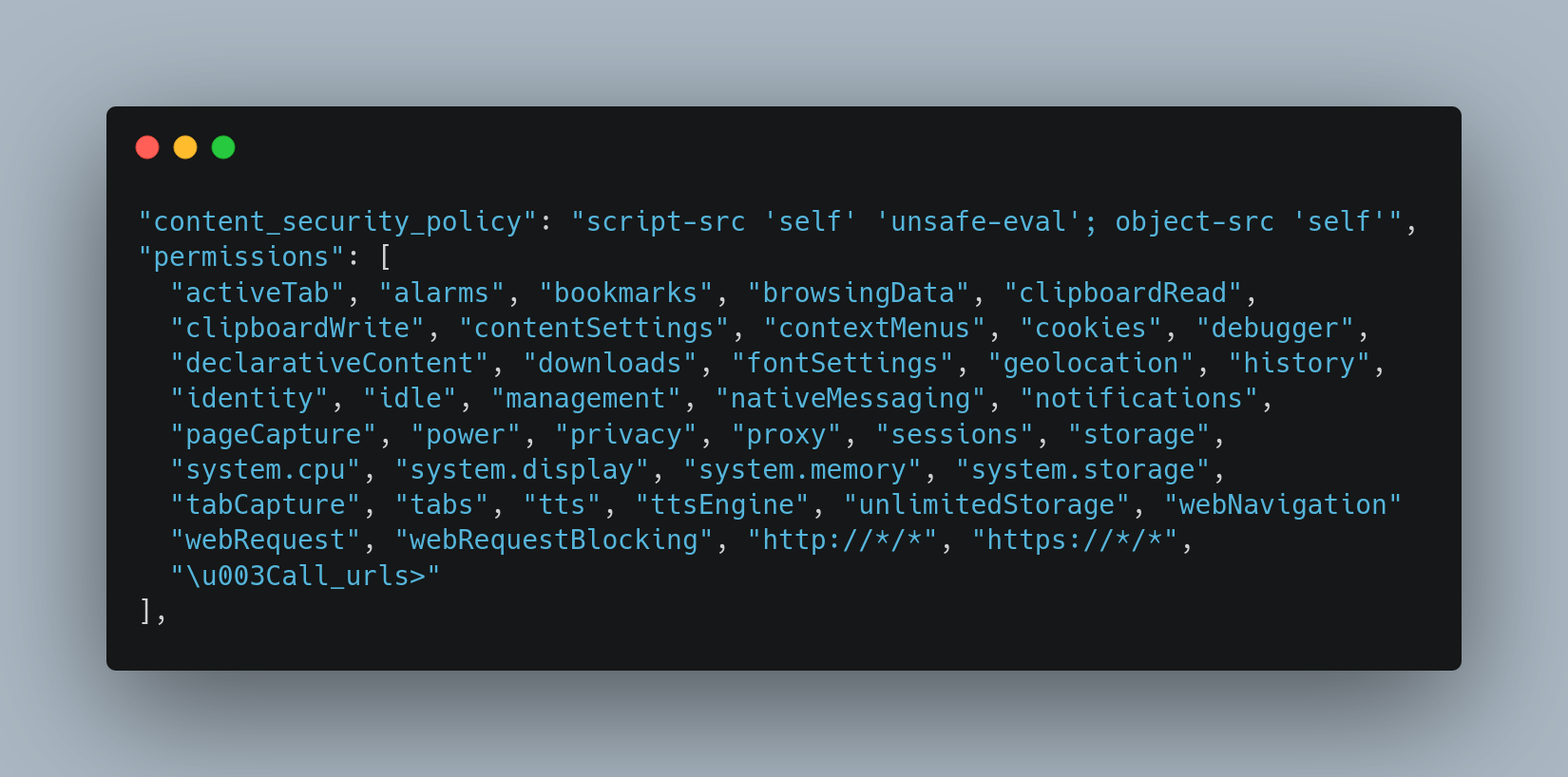

Well, access to extension privileges of course. Browser extensions usually have lots of those, typically explicitly defined in the permissions entry of the extension manifest, but some are granted implicitly. Reason enough to take a closer look at some of these permissions and their potential for abuse.

Note: This article is part of a series on the basics of browser extension security. It’s meant to provide you with some understanding of the field and serve as a reference for my more specific articles. You can browse the extension-security-basics category to see other published articles in this series.

Contents

The crown jewels: host-based permissions

Have a look at the permissions entry of your favorite extension’s manifest. Chances are, you will find entries like the following there:

"permissions": [

"*://*/*"

]

Or:

"permissions": [

"http://*/*",

"https://*/*"

]

Or:

"permissions": [

"<all_urls>"

]

While these three variants aren’t strictly identical, from the security security point of view the differences don’t matter: this extension requests access to each and every website on the web.

Making requests

When regular websites use XMLHttpRequest or fetch API, they are restricted to requesting data from the own website only. Other websites are out of reach by default, unless these websites opt in explicitly by means of CORS.

For browser extensions, host-based permissions remove that obstacle. A browser extension can call fetch("https://gmail.com/") and get a response back. And this means that, as long as you are currently logged into GMail, the extension can download all your emails. It can also send a request instructing GMail to send an email in your name.

It’s similar with your social media accounts and anything else that can be accessed without entering credentials explicitly. You think that your Twitter data is public anyway? But your direct messages are not. And a compromised browser extension can potentially send tweets or direct messages in your name.

The requests can be initiated by any extension page (e.g. the persistent background page). On Firefox host-based permissions allow content scripts to make arbitrary requests as well. There are no visual clues of an extension performing unexpected requests, if an extension turns malicious users won’t usually notice.

Watching tab updates

Host-based permissions also unlock “advanced” tabs API functionality. They allow the extension to call tabs.query() and not only get a list of user’s browser tabs back but also learn which web page (meaning address and title) is loaded.

Not only that, listeners like tabs.onUpdated become way more useful as well. These will be notified whenever a new page loads into a tab.

So a compromised or malicious browser extension has everything necessary to spy on the user. It knows which web pages the user visits, how long they stay there, where they go then and when they switch tabs. This can be misused for creating browsing profiles (word is, these sell well) – or by an abusive ex/employer/government.

Running content scripts

We’ve already seen a content script and some of its potential to manipulate web pages. However, content scripts aren’t necessarily written statically into the extension manifest. Given sufficient host-based permissions, extensions can also load them dynamically by calling tabs.executeScript() or scripting.executeScript().

Both APIs allow executing not merely files contained in the extensions as content scripts but also arbitrary code. The former allows passing in JavaScript code as a string while the latter expects a JavaScript function which is less prone to injection vulnerabilities. Still, both APIs will wreak havoc if misused.

In addition to the capabilities above, content scripts could for example intercept credentials as these are entered into web pages. Another classic way to abuse them is injecting advertising on each an every website. Adding scam messages to abuse credibility of news websites is also possible. Finally, they could manipulate banking websites to reroute money transfers.

Implicit privileges

Some extension privileges don’t have to be explicitly declared. One example is the tabs API: its basic functionality is accessible without any privileges whatsoever. Any extension can be notified when you open and close tabs, it merely won’t know which website these tabs correspond with.

Sounds too harmless? The tabs.create() API is somewhat less so. It can be used to create a new tab, essentially the same as window.open() which can be called by any website. Yet while window.open() is subject to the pop-up blocker, tabs.create() isn’t. An extension can create any number of tabs whenever it wants.

If you look through possible tabs.create() parameters, you’ll also notice that its capabilities go way beyond what window.open() is allowed to control. And while Firefox doesn’t allow data: URIs to be used with this API, Chrome has no such protection. Use of such URIs on the top level has been banned due to being abused for phishing.

tabs.update() is very similar to tabs.create() but will modify an existing tab. So a malicious extension can for example arbitrarily load an advertising page into one of your tabs, and it can activate the corresponding tab as well.

Webcam, geolocation and friends

You probably know that websites can request special permissions, e.g. in order to access your webcam (video conferencing tools) or geographical location (maps). It’s features with considerable potential for abuse, so users each time have to confirm that they still want this.

Not so with browser extensions. If a browser extension wants access to your webcam or microphone, it only needs to ask for permission once. Typically, an extension will do so immediately after being installed. Once this prompt is accepted, webcam access is possible at any time, even if the user isn’t interacting with the extension at this point. Yes, a user will only accept this prompt if the extension really needs webcam access. But after that they have to trust the extension not to record anything secretly.

With access to your exact geographical location or contents of your clipboard, granting permission explicitly is unnecessary altogether. An extension simply adds geolocation or clipboard to the permissions entry of its manifest. These access privileges are then granted implicitly when the extension is installed. So a malicious or compromised extension with these privileges can create your movement profile or monitor your clipboard for copied passwords without you noticing anything.

Other means of exfiltrating browsing data

Somebody who wants to learn about the user’s browsing behavior, be it an advertiser or an abusive ex, doesn’t necessarily need host-based permissions for that. Adding the history keyword to the permissions entry of the extension manifest grants access to the history API. It allows retrieving the user’s entire browsing history all at once, without waiting for the user to visit these websites again.

The bookmarks permission has similar abuse potential, this one allows reading out all bookmarks via the bookmarks API. For people using bookmarks, their bookmarks collection and bookmark creation timestamps tell a lot about this user’s preferences.

The storage permission

We’ve already seen our example extension use the storage permission to store a message text. This permission looks harmless enough. The extension storage is merely a key-value collection, very similar to localStorage that any website could use. Sure, letting arbitrary websites access this storage is problematic if some valuable data is stored inside. But what if the extension is only storing some basic settings?

You have to remember that one basic issue of online advertising is reliably recognizing visitors. If you visit site A, advertisers will want to know whether you visited site B before and what you’ve bought there. Historically, this goal has been achieved via the cookies mechanism.

Now cookies aren’t very reliable. Browsers are giving users much control over cookies, and they are increasingly restricting cookie usage altogether. So there is a demand for cookie replacements, which led to several “supercookie” approaches to be designed: various pieces of data related to the user’s system leaked by the browser are thrown together to build a user identifier. We’ve seen this escalate into a cat and mouse game between advertisers and browser vendors, the former constantly looking for new identifiers while the latter attempt to restrict user-specific data as much as possible.

Any advertiser using supercookies will be more than happy to throw extension storage into the mix if some browser extension exposes it. It allows storing a persistent user identifier much like cookies do. But unlike with cookies, none of the restrictions imposed by browser vendors will apply here. And the user won’t be able to remove this identifier by any means other than uninstalling the problematic extension.

More privileges

The permissions entry of the extension manifest can grant more privileges. It’s too many to cover all of them here, the nativeMessaging permission in particular will be covered in a separate article. MDN provides an overview of what permissions are currently supported.

Why not restrict extension privileges?

Google’s developer policies explicitly prohibit requesting more privileges that necessary for the extension to function. In my experience this rule in fact works. I can only think of one case where a browser extension requested too many privileges, and this particular extension was being distributed with the browser rather than via some add-on store.

The reason why the majority of popular extensions request a very far-reaching set of privileges is neither malice nor incompetence. It’s rather a simple fact: in order to do something useful you need the privileges to do something useful. Extensions restricted to a handful of websites are rarely interesting enough, they need to make an impact on all of the internet to become popular. Extensions that ask you to upload or type things in manually are inconvenient, so popular extensions request webcam/geolocation/clipboard access to automate the process.

In some cases browsers could do better to limit the abuse potential of extension privileges. For example, Chrome allows screen recording via tabCapture or desktopCapture APIs. The abuse potential is low because the former can only be started as a response to a user action (typically clicking the extension icon) whereas the latter brings up a prompt to select the application window to be recorded. Both are sufficient to prevent extensions from silently starting to record in the background. Any of these approaches would have worked to limit the abuse potential of webcam access.

Such security improvements have the tendency to make extensions less flexible and less user-friendly however. A good example here is the activeTab permission. Its purpose is to make requesting host privileges for the entire internet unnecessary. Instead, the extension can access the current tab when the extension is explicitly activated, typically by clicking its icon.

That approach works well for some extensions, particularly those where the user needs to explicitly trigger an action. It doesn’t work in scenarios where extensions have to perform their work automatically however (meaning being more convenient for the user) or where the extension action cannot be executed immediately and requires preparation. So in my extension survey, I see an almost equal split: 19.5% of extensions using activeTab permission and 19.1% using host permissions for all of the internet.

But that does not account for the extension’s popularity. If I only consider the more popular extensions, the ones with 10,000 users and more, things change quite considerably. With 22% the proportion of the extensions using activeTab permission increases only slightly. Yet a whooping 33.7% of the popular extensions ask for host permissions for each and every website.

Comments