In the previous article we discussed extension privileges. And as we know from another article, extension pages are the extension context with full access to these privileges. So if someone were to attack a browser extension, attempting Remote Code Execution (RCE) in an extension page would be the obvious thing to do.

In this article we’ll make some changes to the example extension to make such an attack against it feasible. But don’t be mistaken: rendering our extension vulnerable requires actual work, thanks to the security measures implemented by the browsers.

This doesn’t mean that such attacks are never feasible against real-world extensions. Sometimes even these highly efficient mechanisms fail to prevent a catastrophic vulnerability. And then there are of course extensions explicitly disabling security mechanisms, with similarly catastrophic results. Ironically, both of these examples are supposed security products created by big antivirus vendors.

Note: This article is part of a series on the basics of browser extension security. It’s meant to provide you with some understanding of the field and serve as a reference for my more specific articles. You can browse the extension-security-basics category to see other published articles in this series.

Contents

What does RCE look like?

Extension pages are just regular HTML pages. So what we call Remote Code Execution here, is usually called a Cross-site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability in other contexts. Merely the impact of such vulnerabilities is typically more severe with browser extensions.

A classic XSS vulnerability would involve insecurely handling untrusted HTML code:

var div = document.createElement("div");

div.innerHTML = untrustedData;

document.body.appendChild(div);

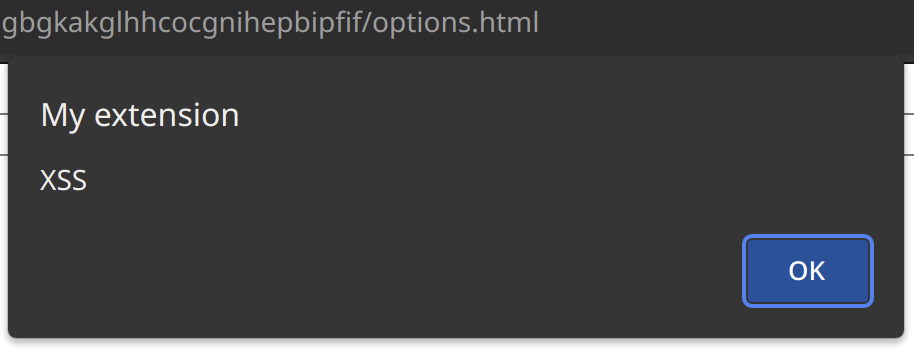

If an attacker can decide what kind of data is assigned to innerHTML here, they could choose a value like <img src="x" onerror="alert('XSS')">. Once that image is added to the document, the browser will attempt to load it. The load fails, which triggers the error event handler. And that handler is defined inline, meaning that the JavaScript code alert('XSS') will run. So you get a message indicating successful exploitation:

And here is your first hurdle: the typical attack target is the background page, thanks to how central it is to most browser extensions. Yet the background page isn’t visible, meaning that it has little reason to deal with HTML code.

What about pages executing untrusted code directly then? Something along the lines of:

eval(untrustedData);

At the first glance, this looks similarly unlikely. No developer would actually do that, right?

Actually, they would if they use jQuery which has an affinity for running JavaScript code as an unexpected side-effect.

Modifying the example extension

I’ll discuss all the changes to the example extension one by one. But you can download the ZIP file with the complete extension source code here.

Before an extension page can run malicious code, this code has to come from somewhere. Websites, malicious or not, cannot usually access extension pages directly however. So they have to rely on extension content scripts to pass malicious data along. This separation of concerns reduces the attack surface considerably.

But let’s say that our extension wanted to display the price of the item currently viewed. The issue: the content script cannot download the JSON file with the price. That’s because the content script itself runs on www.example.com whereas JSON files are stored on data.example.com, so same-origin policy kicks in.

No problem, the content script can ask the background page to download the data:

chrome.runtime.sendMessage({

type: "check_price",

url: location.href.replace("www.", "data.") + ".json"

}, response => alert("The price is: " + response));

Next step: the background page needs to handle this message. And extension developers might decide that fetch API is too complicated, which is why they’d rather use jQuery.ajax() instead. So they do the following:

chrome.runtime.onMessage.addListener((request, sender, sendResponse) =>

{

if (request.type == "check_price")

{

$.get(request.url).done(data =>

{

sendResponse(data.price);

});

return true;

}

});

Looks simple enough. The extension needs to load the latest jQuery 2.x library as a background script and request the permissions to access data.example.com, meaning the following changes to manifest.json:

{

…

"permissions": [

"storage",

"https://data.example.com/*"

],

…

"background": {

"scripts": [

"jquery-2.2.4.min.js",

"background.js"

]

},

…

}

This appears to work correctly. When the content script executes on https://www.example.com/my-item it will ask the background page to download https://data.example.com/my-item.json. The background page complies, parses the JSON data, gets the price field and sends it back to the content script.

The attack

You might wonder: where did we tell jQuery to parse JSON data? And we actually didn’t. jQuery merely guessed that we want it to parse JSON because we downloaded a JSON file.

What happens if https://data.example.com/my-item.json is not a JSON file? Then jQuery might interpret this data as any one of its supported data types. By default those are: xml, json, script or html. And you can probably spot the issue already: script type is not safe.

So if a website wanted to exploit our extension, the easiest way would be to serve a JavaScript file (MIME type application/javascript) under https://data.example.com/my-item.json. One could use the following code for example:

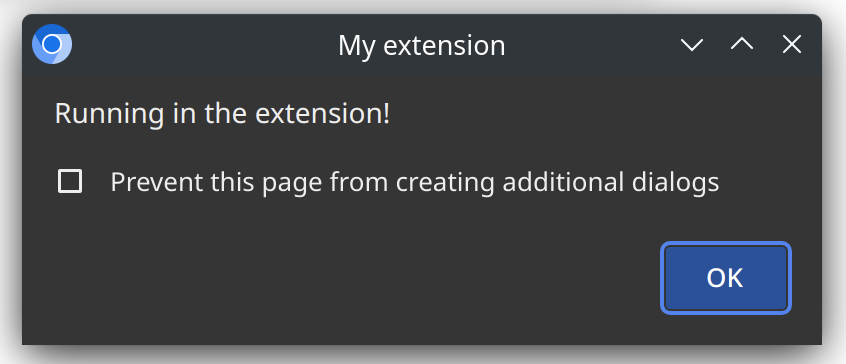

alert("Running in the extension!");

Will jQuery then try to run that script inside the background page? You bet!

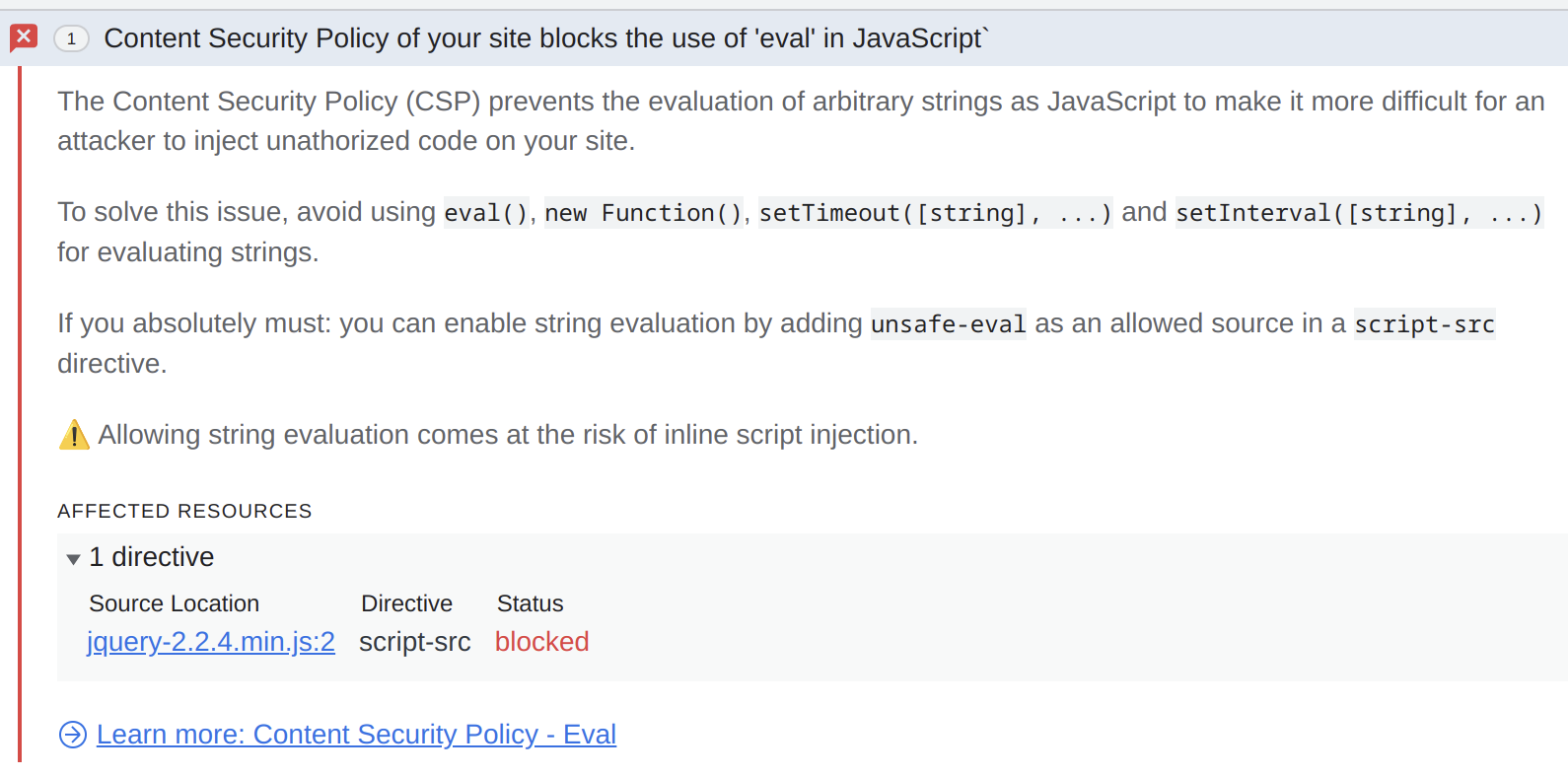

But the browser saves the day once again. The Developer Tools display the following issue for the background page now:

Note: There is a reason why I didn’t use jQuery 3.x. The developers eventually came around and disabled this dangerous behavior for cross-domain requests. In jQuery 4.x it will even be disabled for all requests. Still, jQuery 2.x and even 1.x remain way too common in browser extensions.

Making the attack succeed

The Content Security Policy (CSP) mechanism which stopped this attack is extremely effective. The default setting for browser extension pages is rather restrictive:

script-src 'self'; object-src 'self';

The script-src entry here determines what scripts can be run by extension pages. 'self' means that only scripts contained in the extension itself are allowed. No amount of trickery will make this extension run a malicious script on an extension page. This protection renders all vulnerabilities non-exploitable or at least reduces their severity considerably. Well, almost all vulnerabilities.

That’s unless an extension relaxes this protection, which is way too common. For example, some extensions will explicitly change this setting in their manifest.json file to allow eval() calls:

{

…

"content_security_policy": "script-src 'self' 'unsafe-eval'; object-src 'self';",

…

}

Protection is gone and the attack described above suddenly works!

Do I hear you mumble “cheating”? “No real extension would do that” you say? I beg to differ. In my extension survey 7.9% of the extensions use 'unsafe-eval' to relax the default Content Security Policy setting.

In fact: more popular extensions are more likely to be the offenders here. When looking at extensions with more than 10,000 users, it’s already 12.5% of them. And for extensions with at least 100,000 users this share goes up to 15.4%.

Further CSP circumvention approaches

Edit (2022-08-24): This section originally mentioned 'unsafe-inline' script source. It is ignored for browser extensions however, so that it isn’t actually relevant in this context.

It doesn’t always have to be the 'unsafe-eval' script source which essentially drops all defenses. Sometimes it is something way more innocuous, such as adding the some website as a trusted script source:

{

…

"content_security_policy": "script-src 'self' https://example.com/;"

…

}

With example.com being some big name’s code hosting or even the extension owner’s very own website, it certainly can be trusted? How likely is it that someone will hack that server only to run some malicious script in the extension?

Actually, hacking the server often isn’t necessary. Occasionally, example.com will contain a JSONP endpoint or something similar. For example, https://example.com/get_data?callback=ready might produce a response like this:

ready({...some data here...});

Attackers would attempt to manipulate this callback name, e.g. loading https://example.com/get_data?callback=alert("XSS")// which will result in the following script:

alert("XSS")//({...some data here...});

That’s it, now example.com can be used to produce a script with arbitrary code and CSP protection is no longer effective.

Side-note: These days JSONP endpoints usually restrict callback names to alphanumeric characters only, to prevent this very kind of abuse. However, JSONP endpoints without such protection are still too common.

Edit (2022-08-25): The original version of this article mentioned open redirects as another CSP circumvention approach. Current browser versions check redirect target against CSP as well however.

Recommendations for developers

So if you are an extension developer and you want to protect your extension against this kind of attacks, what can you do?

First and foremost: let Content Security Policy protect you. Avoid adding 'unsafe-eval' at any cost. Rather than allowing external script sources, bundle these scripts with your extension. If you absolutely cannot avoid loading external scripts, try to keep the list short.

And then there is the usual advise to prevent XSS vulnerabilities:

- Don’t mess with HTML code directly, use safe DOM manipulation methods such as createElement(), setAttribute(), textContent.

- For more complicated user interfaces use safe frameworks such as React or Vue.

- Do not use jQuery.

- If you absolutely have to handle dynamic HTML code, always pass it through a sanitizer such as DOMPurify and soon hopefully the built-in HTML Sanitizer API.

- When adding links dynamically, always make sure that the link target starts with

https://or at leasthttp://so that nobody can smuggle in ajavascript:link.

Comments