A while back I wrote about a bunch of vulnerabilities in McAfee WebAdvisor, a component of McAfee antivirus products which is also available as a stand-alone application. Part of the fix was adding a bunch of pages to the extension which were previously hosted on siteadvisor.com, generally a good move. However, when I looked closely I noticed a Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) vulnerability in one of these pages (CVE-2019-3670).

Now an XSS vulnerability in a browser extension is usually very hard to exploit thanks to security mechanisms like Content Security Policy and sandboxing. These mechanisms were intact for McAfee WebAdvisor and I didn’t manage to circumvent them. Yet I still ended up with a proof of concept that demonstrated how attackers could gain local administrator privileges through this vulnerability, something that came as a huge surprise to me as well.

Contents

Summary of the findings

Both the McAfee WebAdvisor browser extension and the HTML-based user interface of its UIHost.exe application use the jQuery library. This choice of technology proved quite fatal: not only did it contribute to both components being vulnerable to XSS, it also made the vulnerability exploitable in the browser extension where existing security mechanisms would normally make exploitation very difficult to say the least.

In the end, a potential attacker could go from a reflective XSS vulnerability in the extension to a persistent XSS vulnerability in the application to writing arbitrary Windows registry values. The latter can then be used to run any commands with privileges of the local system’s administrator. The attack could be performed by any website and the required user interaction would be two clicks anywhere on the page.

At the time of writing, McAfee closed the XSS vulnerability in the WebAdvisor browser extensions and users should update to version 8.0.0.37123 (Chrome) or 8.0.0.37627 (Firefox) ASAP. From the look of it, the XSS vulnerability in the WebAdvisor application remains unaddressed. The browser extensions no longer seem to have the capability to add whitelist entries here which gives it some protection for now. It should still be possible for malware running with user’s privileges to gain administrator access through it however.

The initial vulnerability

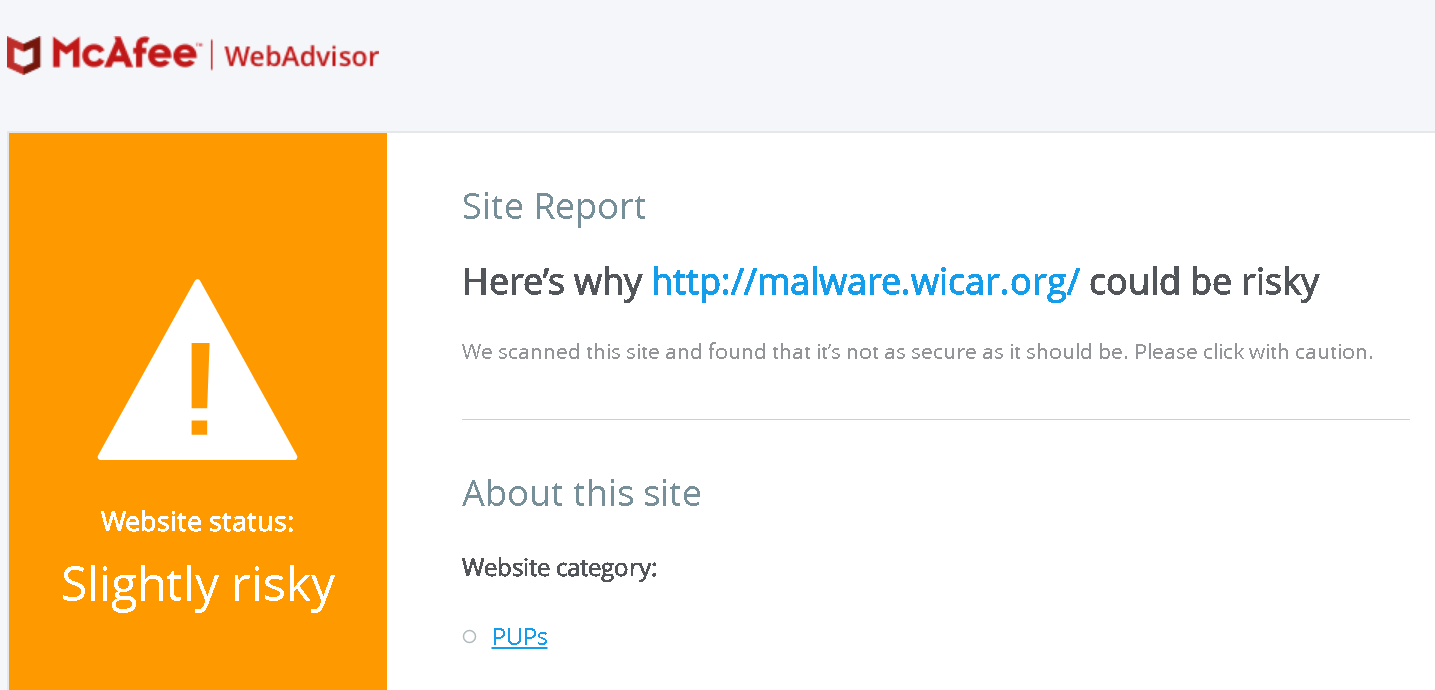

When McAfee WebAdvisor prevents you from accessing a malicious page, a placeholder page is displayed instead. It contains a “View site report” link which brings you to the detailed information about the site. Here is what this site report looks like for the test website malware.wicar.org:

This page happens to be listed in the extensions web accessible resources, meaning that any website can open it with any parameters. And the way it handles the url query parameter is clearly problematic. The following code has been paraphrased to make it more readable:

const url = new URLSearchParams(window.location.search).get("url");

const uri = getURI(url);

const text = localeData(`site_report_main_url_${state}`, [`<span class="main__url">${uri}</span>`]);

$("#site_report_main_url").append(text);This takes a query parameter, massages it slightly (function getURI() merely removes the query/anchor part from a URL) and then inserts it into a localization string. The end result is added to the page by means of jQuery.append(), a function that will parse HTML code and insert the result into the DOM. At no point does this ensure that HTML code in the parameter won’t cause harm.

So a malicious website could open site_report.html?url=http://malware.wicar.org/<marquee>horrible</marquee> and subject the user to abhorrent animations. But what else could it do?

Exploiting XSS without running code

Any attempts to run JavaScript code through this vulnerability are doomed. That’s because the extension’s Content Security Policy looks like this:

"content_security_policy": "script-src 'self' 'unsafe-eval'; object-src 'self'",Why the developers relaxed the default policy by adding 'unsafe-eval' here? Beats me. But it doesn’t make attacker’s job any easier, without any eval() or new Function() calls in this extension. Not even jQuery will call eval() for inline scripts, as newer versions of this library will create actual inline scripts instead – something that browsers will disallow without an 'unsafe-inline' keyword in the policy.

So attackers have to use JavaScript functionality which is already part of the extension. The site report page has no interesting functionality, but the placeholder page does. This one has an “Accept the Risk” button which will add a blocked website to the extension’s whitelist. So my first proof of concept page used the following XSS payload:

<script type="module" src="chrome-extension://fheoggkfdfchfphceeifdbepaooicaho/block_page.js">

</script>

<button id="block_page_accept_risk"

style="position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; bottom: 0; width: 100%;">

Dare to click!

</button>This loads the extension’s block_page.js script so that it becomes active on the site report page. And it adds a button that this script will consider “Accept the Risk” button – only that the button’s text and appearance are freely determined by the attacker. Here, the button is made to cover all of page’s content, so that clicking anywhere will trigger it and produce a whitelist entry.

All the non-obvious quirks here are related to jQuery. Why type="module" on the script tag? Because jQuery will normally download script contents and turn them into an inline script which will then be blocked by the Content Security Policy. jQuery leaves ECMAScript modules alone however and these can execute normally.

Surprised that the script executes? That’s because jQuery doesn’t simply assign to innerHTML, it parses HTML code into a document fragment before inserting the results into the document.

Why don’t we have to generate any event to make block_page.js script attach its event listeners? That’s because the script relies on jQuery.ready() which will fire immediately if called in a document that already finished loading.

Getting out of the sandbox…

Now we’ve seen the general approach of exploiting existing extension functionality in order to execute actions without any own code. But are there actions that would produce more damage than merely adding whitelist entries? When looking through extension’s functionality, I noticed an unused options page – extension configuration would normally be done by an external application. That page and the corresponding script could add and remove whitelist entries for example. And I noticed that this page was vulnerable to XSS via malicious whitelist entries.

So there is another XSS vulnerability which wouldn’t let attackers execute any code, now what? But that options page is eerily similar to the one displayed by the external application. Could it be that the application is also displaying an HTML-based page? And maybe, just maybe, that page is also vulnerable to XSS? I mean, we could use the following payload to add a malicious whitelist entry if the user clicks somewhere on the page:

<script type="module" src="chrome-extension://fheoggkfdfchfphceeifdbepaooicaho/settings.js">

</script>

<button id="add-btn"

style="position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; bottom: 0; width: 100%;">

Dare to click!

</button>

<input id="settings_whitelist_input"

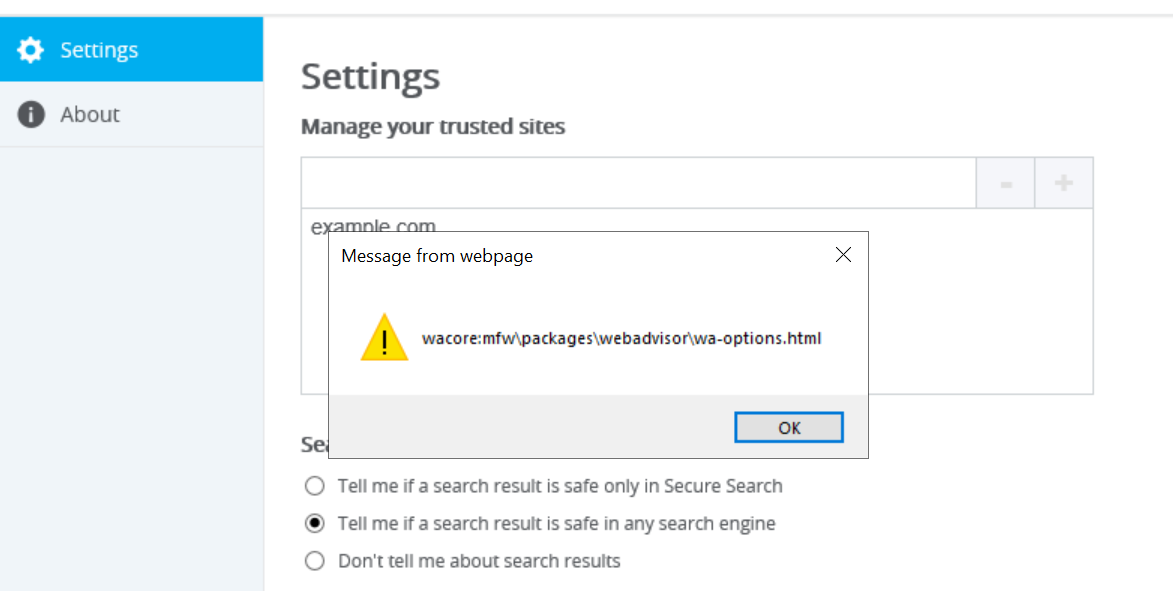

value="example.com<script>alert(location.href)</script>">And if we then open WebAdvisor options…

This is no longer the browser extension, it’s the external UIHost.exe application. The application has an HTML-based user interface and it is also using jQuery to manipulate it, not bothering with XSS prevention of any kind. No Content Security Policy is stopping us here any more, anything goes.

Of course, attackers don’t have to rely on the user opening options themselves. They can rather instrument further extension functionality to open options programmatically. That’s what my proof of concept page did: first click would add a malicious whitelist entry, second click opened the options then.

… and into the system

It’s still regular JavaScript code that is executing in UIHost.exe, but it has access to various functions exposed via window.external. In particular, window.external.SetRegistryKey() is very powerful, it allows writing any registry keys. And despite UIHost.exe running with user privileges, this call succeeds on HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE keys as well – presumably asking the McAfee WebAdvisor service to do the work with administrator privileges.

So now attackers only need to choose a registry key that allows them to run arbitrary code. My proof of concept used the following payload in the end:

window.external.SetRegistryKey('HKLM',

'SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run',

'command',

'c:\\windows\\system32\\cmd.exe /k "echo Hi there, %USERNAME%!"',

'STR',

'WOW64',

false),

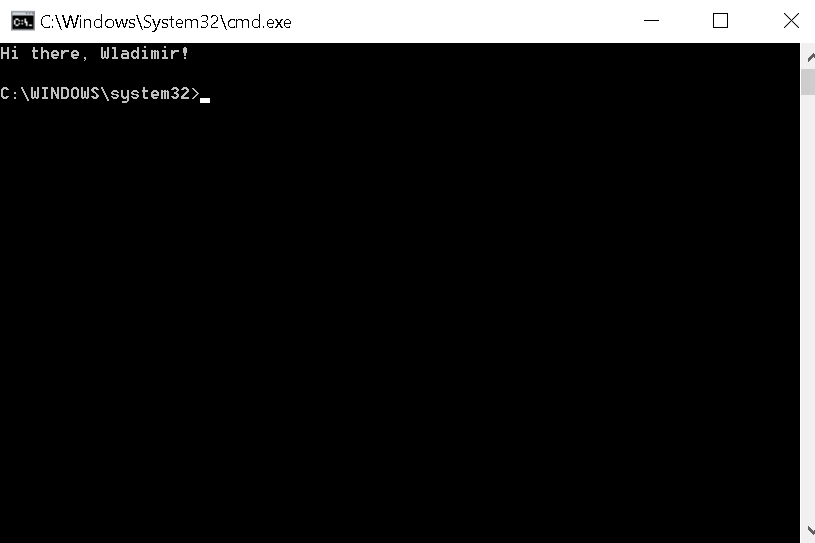

window.external.Close()This calls window.external.Close() so that the options window closes immediately and the user most likely won’t even see it. But it also adds a command to the registry that will be run on startup. So when any user logs on, they will get this window greeting them:

Yes, I cheated. I promised administrator privileges, yet this command executes with user’s privileges. In fact, with privileges of any user of the affected system who dares to log on. Maybe you’ll just believe me that attackers who can write arbitrary values to the registry can achieve admin privileges? No? Ok, there is this blog post which explains how writing to \SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows NT\CurrentVersion\Image File Execution Options\wsqmcons.exe and adding a “debugger” will get you there.

Conclusions

The remarkable finding here: under some conditions, not even a restrictive Content Security Policy value will prevent an XSS vulnerability from being exploited. And “some conditions” in this particular case means: using jQuery. jQuery doesn’t merely encourage a coding style that’s prone to introducing XSS vulnerabilities, here both in the browser extension and the standalone application. Its unusual handling of HTML code also means that <script> tags will be allowed to execute, unlike when a usual assignment to innerHTML is used. Without that, this vulnerability likely wouldn’t be exploitable.

Interestingly, the use of jQuery.ready() also contributed to this issue becoming exploitable. If the code used DOMContentLoaded event or a similar initialization mechanism, there would be no way to make it initialize here. Yet jQuery.ready() handler is guaranteed to run, and so an additional script would initialize regardless of when it loaded.

So the first recommendation to avoid such issues is definitely: use a modern framework that is inherently safe. For example, it’s far harder to introduce XSS vulnerabilities with React or Vue – normally no innerHTML or equivalents are used here. These frameworks will also only attach event listeners to elements that they created themselves, any elements injected into the DOM externally will stay without functionality.

It’s also important to have defense in depth however. HTML-based user interfaces for applications seem to be rather popular with antivirus vendors. It should be possible to ensure that an XSS vulnerability here doesn’t result in catastrophic failure however. With Internet Explorer being used under the hood, Content Security Policy doesn’t seem to be an option. But at least the functionality exposed via window.external can be limited in what it can do. For example, there is no reason to provide access to the entire registry here when the function is only needed to install browser extensions.

Timeline

- 2019-11-27: Reported vulnerability to McAfee via email, subject to 90 days deadline.

- 2019-12-02: Got confirmation that the report was received, after asking about it.

- 2020-02-03: Reminded McAfee of the approaching deadline, seeing that the issue is unresolved.

- 2020-02-05: McAfee notified me that the Chrome extension has been fixed and remaining issues will be resolved shortly.

- 2020-02-19: Again reminded McAfee of the deadline, seeing that issue is unresolved in Firefox extension and application.

- 2020-02-21: McAfee published their writeup on CVE-2019-3670.

- 2020-02-24: Received confirmation from McAfee that a fix for the Firefox extension has been released.

Comments

Hi there,

Everytime when I am opening a new window, I have a pop-up from McAfee. I wenth through internet and I found out I have an extension with the following file " fheoggkfdfchfphceeifdbepaooicaho" .

I have a trojan in my computer? How to clean my computer then? if it is not a virus please do let me know.

Thanks. I am looking forward to hearing from you.

Best regards, John.

fheoggkfdfchfphceeifdbepaooicaho is the identifier of the legitimate McAfee WebAdvisor extension. But that’s all I can tell from the information you provided. This is really not the place to ask for tech support, you should probably look for a vendor offering it in your area.