Note: This article is also available in Korean.

As discussed before, South Korea’s banking websites demand installation of various so-called security applications. At the same time, we’ve seen that these applications like TouchEn nxKey and IPinside lack auto-update functionality. So even in case of security issues, it is almost impossible to deliver updates to users timely.

And that’s only two applications. Korea’s banking websites typically expect around five applications, and it will be different applications for different websites. That’s a lot of applications to install and to keep up-to-date.

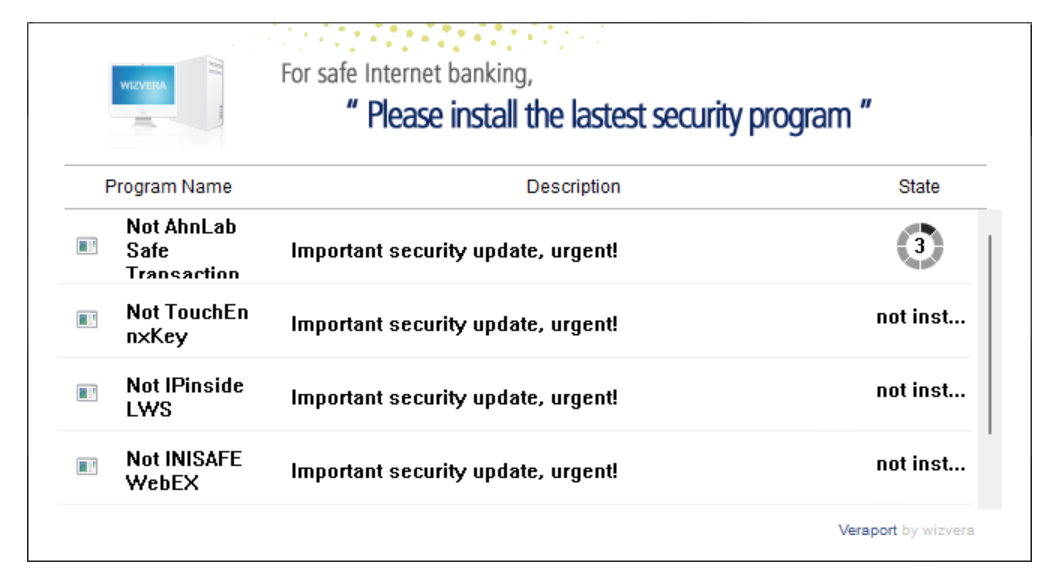

Luckily, the Veraport application by Wizvera will take care of that. This application will automatically install everything necessary to use a particular website. And it will also install updates if deemed necessary.

If this sounds like a lot of power: that’s because it is. And so Veraport already made the news as the vehicle of an attack by North Korean hackers.

Back then everybody was quick to shift the blame to the compromised web servers. I now took a deeper dive into how Veraport works and came to the conclusion: its approach is inherently dangerous.

As of Veraport 3.8.6.5 (released on February 28), all the reported security issues seem to be fixed. Getting users to update will take a long time however. Also, the dangerous approach of allowing Veraport customers to distribute arbitrary software remains of course.

Contents

Summary of the findings

Veraport signs the policy files determining which applications are to be installed from where. While the cryptography here is mostly sane, the approach suffers from a number of issues:

- One root certificate still used for signature validation is using MD5 hashing and a 1024 bit strong RSA key. Such certificates have been deprecated for over a decade.

- HTTPS connection for downloads is not being enforced. Even when HTTPS is used, server certificate is not validated.

- Integrity of downloaded files is not validated correctly. Application signature validation is trivially circumvented, and while hash-based validation is possible this functionality is essentially unused.

- Even if integrity validation weren’t easily circumvented, Veraport leaves the choice to the user as to whether to proceed with a compromised binary.

- Download and installation of an application can be triggered without user interaction and without any visible clues.

- Individual websites (e.g. banking) are still responsible for software distribution and will often offer outdated applications, potentially with known security issues.

- Each and every Veraport customer is in possession of a signing certificate that, if compromised, can sign arbitrary malicious policies.

- There is no revocation mechanism to withdraw known leaked signing certificates or malicious policies.

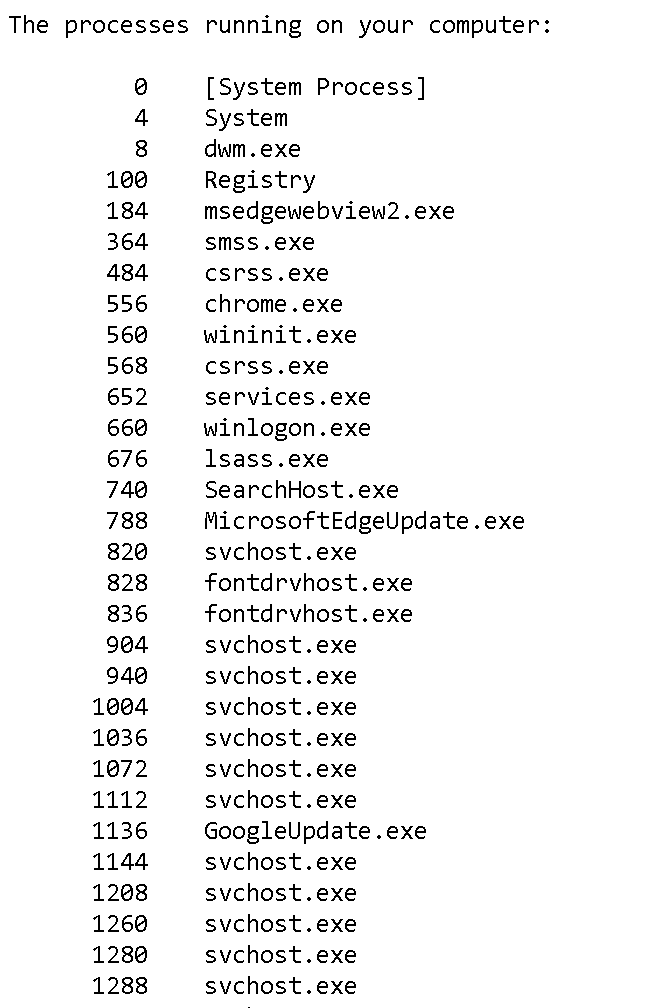

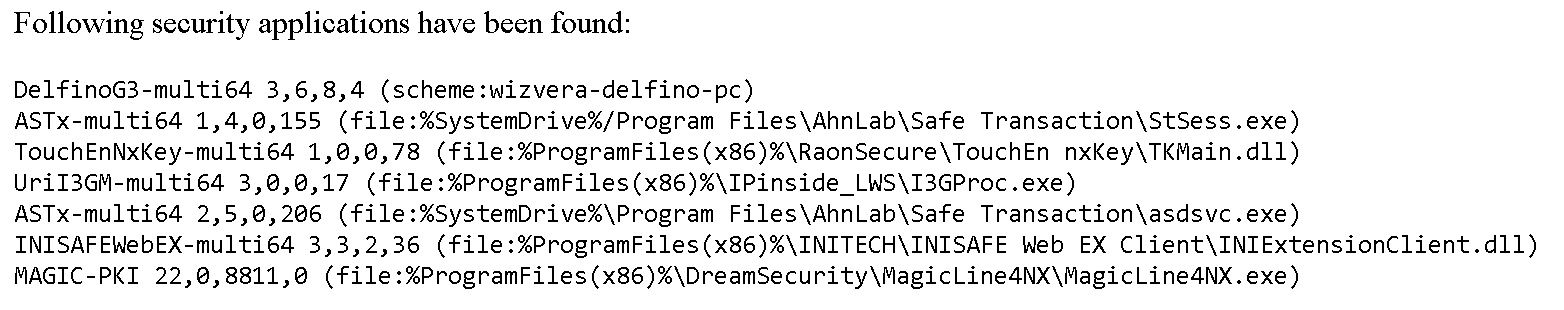

In addition to that, Veraport’s local web server on https://127.0.0.1:16106 contains vulnerabilities amounting to persistent Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) among other things. It will expose the full list of the processes running on the user’s machine to any website asking. For security applications it will also expose the application version.

Finally, Veraport is also built on top of a number of outdated open-source libraries with known vulnerabilities. For example, it uses OpenSSL 1.0.2j (released 2016) for its web server and for signature validation. OpenSSL vulnerabilities are particularly well-documented – it’s at least 3 known high-severity and 13 known moderate-severity vulnerabilities for this version.

The local web server itself is mongoose 5.5 (released in 2014). And parsing of potentially malicious JSON data received from websites is done via JsonCpp 0.5.0 (released 2010). Yes, that’s almost 13 years old. Yes, current version is JsonCpp 1.9.5 which has seen plenty of security improvements.

How banking websites distribute applications

Login websites of South Korean banks run JavaScript code from SDKs belonging to various so-called security applications. Each such SDK will first check whether the application is present on the user’s computer. If it isn’t, the typical action is redirecting the user to a download page.

![Screenshot of a page titled “Install Security Program.” Below it the text “To access and use services on Busan Bank website, please install the security programs. If your installation is completed, please click Home Page to move to the main page. Click [Download Integrated Installation Program] to start automatica installation. In case of an error message, please click 'Save' and run the downloaded the application.” Below that text the page suggests downloading “Integrated installation (Veraport)” and five individual applications.](/2023/03/06/veraport-inside-koreas-dysfunctional-application-management/applications.png)

This isn’t the software vendor’s download page but rather the bank’s page. It lists all the various applications required and expects you to download them. Typically, the bank’s web server doubles as the download server for the application. Some of the software vendors don’t even have their own download servers.

So it probably comes as no surprise that all banks distribute different versions of the applications, often years behind the current release. Also, it’s very common to find an outdated and hopefully unused installation page. Downloading the application from this page will usually still work, but it will be up to a decade old.

For example, until a few weeks ago the Citibank Korea web page would distribute TouchEn nxKey 1.0.0.75 from 2020 (current version at the time was 1.0.0.78). But if you accidentally got the wrong download page, you would be downloading TouchEn nxKey 1.0.0.5 from 2015.

And while Busan Bank website for example claims to have software packages for Linux and macOS users, these aren’t actually downloadable or you get Windows software. The one Linux package which can be downloaded is from 2015 and relies on NPAPI which isn’t supported by modern browsers.

Obviously, users cannot be expected to deal with this entire mess. And that’s why banks typically also offer something called “integrated installation.” This means downloading Wizvera Veraport application and letting it do everything necessary.

How Wizvera Veraport works

If you expect Veraport to know where to get the latest version of each application and when to update them: that’s of course not it. Instead, Veraport merely automates the task of installing applications. It does exactly what the user would do: downloads each application (usually from the bank’s servers) and runs the installer.

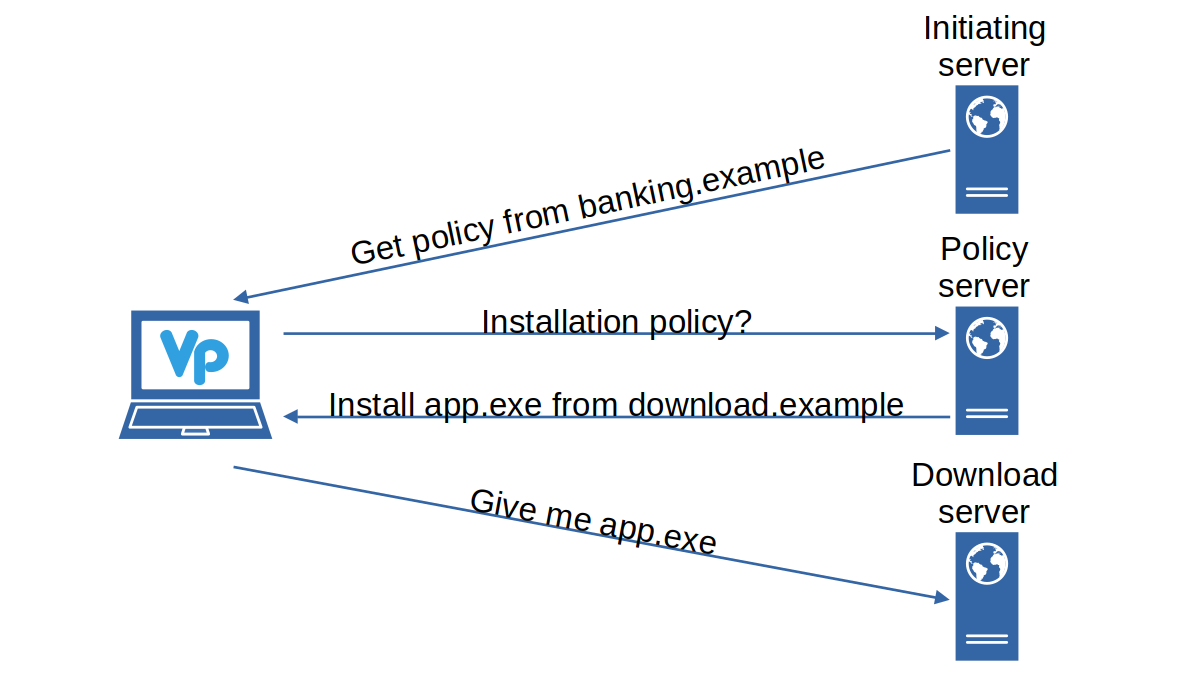

So your banking website will connect to Veraport’s local server on https://127.0.0.1:16106 and send it a JSONP request. It will use a command like getAxInfo to make it download an installation policy from some (typically its own) website:

send_command("getAxInfo", {

"configure": {

"domain": "http://banking.example/",

"axinfourl": "http://banking.example/wizvera/plinfo.html",

"type": "normal",

"language": "eng",

"browser": "Chrome/106.0.0.0",

"forceinstall": "TouchEnNxKeyNo",

}

});

This will make Veraport download and validate a policy file from http://banking.example/wizvera/plinfo.html which is essentially an XML file looking like this:

<pluginInstallInfo>

<version>2.2</version>

<createDate>2022/02/18 17:04:35</createDate>

<allowDomains>www.citibank.co.kr;*.citibank.co.kr;cbolrnd.apac.nsroot.net</allowDomains>

<allowContexts/>

<object type="Must">

<objectName>TouchEnNxKeyNo</objectName>

<displayName>TouchEnNxKey-multi64</displayName>

<objectVersion>1.0.0.73</objectVersion>

<signVerify>confirm</signVerify>

<hashCheck>ignore</hashCheck>

<browserType>Mozilla</browserType>

<objectMIMEType>

file:%ProgramFiles(x86)%\RaonSecure\TouchEn nxKey\TKMain.dll

</objectMIMEType>

<downloadURL>

/3rdParty/raon/TouchEn/nxKey/nxKey/module/

TouchEn_nxKey_Installer_32bit_MLWS_nonadmin.exe /silence

</downloadURL>

<backupURL>

/3rdParty/raon/TouchEn/nxKey/nxKey/module/

TouchEn_nxKey_Installer_32bit_MLWS_nonadmin.exe

</backupURL>

<systemType>64</systemType>

<javascriptURL/>

<objectHash/>

<extInfo/>

<policyInfo/>

<description/>

</object>

<object type="Must">

…

</object>

…

</pluginInstallInfo>

This indicates that TouchEn nxKey is a required application. The objectMIMEType entry allows Veraport to recognize whether the application is currently installed. If it isn’t, the downloadURL and backupURL entries are to be used to download the installer.

Once this data is processed, the initiating website can make Veraport open its user interface:

send_command("show");

What happens next depends on the type configuration parameter passed before. In “manage” mode Veraport will allow the user to choose which applications should be installed. Removing already installed applications is theoretically also possible but didn’t work when I tried. In other modes such as “normal” Veraport will automatically start downloading and installing whatever applications are considered necessary.

Protection against malicious policies

Veraport places no restrictions on initiating servers. Any website can communicate with its local web server, so any website can initiate software installation. What is stopping malicious websites from abusing this functionality to install malware then?

This time it isn’t (only) obfuscation. The policy file needs to be cryptographically signed. And the signer has to be verified by one of Veraport’s two certification authorities hardcoded in the application. So in theory, only Veraport customers can sign such policies, and malicious websites can only attempt to abuse legitimate policies.

Veraport then further restricts which websites are allowed to host such policies. That’s the allowedDomains entry in the policy file above. From what I could tell, the web address parsing here works correctly and doesn’t allow circumvention.

If the policy file contains relative paths under downloadURL and backupURL (very common), these are resolved relative to the location of the policy file. In principle, these security mechanisms combined make sure that even abusing a legitimate policy cannot trigger downloads from untrusted locations.

Holes in the protection

While the measures above provide some basic protection, there are many holes that malicious actors could abuse.

Lack of data protection in transit

Veraport generally does not enforce HTTPS connections. Any of the connections can use unencrypted HTTP, including software downloads. In fact, I’ve not seen a policy using anything other than unencrypted HTTP for the AhnLab Safe Transaction download. When connected to an untrusted network, this download could be replaced by malware.

It is no different with applications that are downloaded via a relative path. While a malicious website cannot (easily) manipulate a policy file, it can initiate a policy download via an unencrypted HTTP connection. All downloads indicated by relative paths will be downloaded via an unencrypted HTTP connection then.

Using HTTPS connections consistently wouldn’t quite solve the issue however. In my tests, Veraport didn’t verify server identity even for HTTPS connections. So even if application download were to happen from https://download.example, on an untrusted network a malicious server could pose as download.example and Veraport would accept it.

Overly wide allowedDomains settings

It seems that Wizvera provides their customers with a signing key, and these sign their policy files themselves. I don’t know whether these customers are provided with any guidelines on how to choose secure settings, particularly when it comes to allowedDomains.

Even looking at the Citibank example above, *.citibank.co.kr means that each and every subdomain of citibank.co.kr can host their policy file. In connection with relative download paths, each subdomain has the potential to distribute malware. And I suspect that there are many such subdomains, some of which might be compromised e.g. via subdomain takeover. The other option is straight out hacking a website, something that apparently already happened in 2020.

I’ve only looked at a few policy files, and this blanket whitelisting of the company’s domain is present in all of them. One was worse however: it also listed multiple IP ranges as allowed. Now I don’t know why a South Korean company would put IP ranges belonging to Abbott Laboratories and US Department of Defense on this list, but they did. And they also listed 127.0.0.1.

Who has the signing keys?

Obviously, Wizvera customers can sign any policy file they like. So if they want to allow example.com website to install malicious.exe – there is nothing stopping them. They only need a valid signing certificate, the use of this certificate isn’t restricted to their website. And the Wizvera website lists many customers:

Hopefully, all these customers realize the kind of power they have been granted and keep the private key of their signing certificate somewhere very secure. If this key falls into the wrong hands, it could be abused to sign malicious policies.

There are many ways for a private key to leak. The company could get hacked, something that happens way too often. They might leak data via an insufficiently protected source code repository or the like. A disgruntled employee might accept a bribe or straight out sell the key to someone malicious. Or some government might ask the company to hand over the key, particularly likely for multinational companies.

And if that happens, Wizvera won’t be able to do anything to prevent abuse. Even if a signing certificate is known to be compromised, the application has no certificate revocation mechanism. There is also no mechanism to block known malicious policies as long as these have a valid signature. The only way to limit the damage would be distributing a new Veraport version, a process that without any autoupdate functionality takes years.

The certification authorities

And that’s abuse of legitimate signing certificates. But what if somebody manages to create their own signing certificate?

That’s not entirely unrealistic, thanks to Veraport accepting two certification authorities:

| Authority name | Validity | Key size | Signature algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|

| axmserver | 2008-11-16 to 2028-11-11 | 1024 | MD5 |

| VERAPORT Root CA | 2020-07-21 to 2050-07-14 | 2048 | SHA256 |

It seems that the older of the two certification authorities was used exclusively until 2020. Using a 1024 bit key and an MD5 signature was long deprecated at this point, with the browsers starting to phase out such certification authorities a decade earlier. Yet there we are in year 2023, and this certification authority is still accepted by Veraport.

Mind you, to my knowledge nobody managed to successfully factorize a 1024 bit RSA key yet. Neither did anyone succeed generating a collision with a given MD5 signature. But both of these scenarios got realistic enough that browsers took preventive measures more than a decade ago already.

And speaking of outdated technology, Microsoft’s requirements for certification authorities say:

Root certificates must expire no more than 25 years after the date of application for distribution.

Reason for this requirement is: the longer a certification authority is around, the more outdated its technological base and the more likely it is to be compromised. So Veraport might want to overthink its newer certification authority’s 30 years life span.

Combining the holes into an exploit

A successful Veraport exploit would be launched from a malicious website. When a user visits it, it would trigger installation of a malicious application without providing any clues to the user. That’s what my proof of concept demonstrated.

Using an existing policy file from a malicious website

As mentioned before, policy files have to be hosted by a particular domain. While this restriction isn’t easily circumvented, one doesn’t need to hack a banking website. Instead, I considered a situation where the network connection isn’t trusted, e.g. open WiFi.

If you connect to someone’s WiFi, they can direct you to their web page. It could look like a captive portal but in fact attempt to exploit Veraport, e.g. by using the existing signed policy file from hanacard.co.kr.

And since they control the network, they can tell your computer that www.hanacard.co.kr has for example the IP address 192.0.2.1. As mentioned above, Veraport won’t realize that 192.0.2.1 isn’t really www.hanacard.co.kr no matter what.

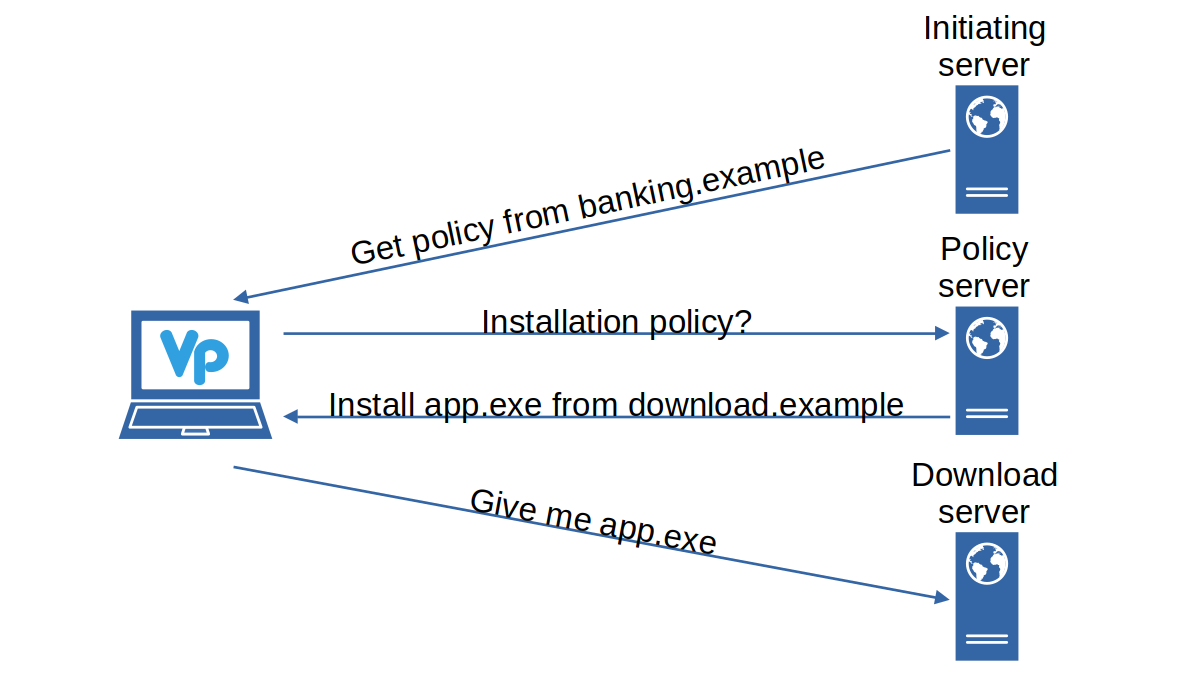

So then the malicious website can trigger Veraport’s automatic installation:

Running a malicious binary

As mentioned before, relative download paths are resolved relative to the policy file. So that “DelphinoG3” application is downloading from “www.hanacard.co.kr” just like the policy file, meaning that it actually comes from a server controlled by the attacker.

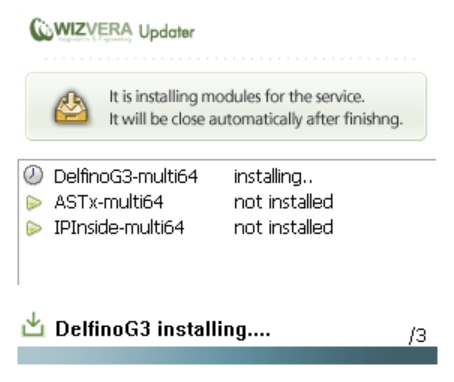

But a malicious application won’t install, at least not immediately:

![A message box saying: It’s wrong signature for DelfinoG3 [0x800B0100,0x800B0100], Disregards this error and continues a progress?](/2023/03/06/veraport-inside-koreas-dysfunctional-application-management/wrong_signature.png)

With this cryptic message, chances are good that the user will click “OK” and allow the malicious application to execute. That’s why security-sensitive decisions should never be left to the user. But what signature does it even mean?

The policy files have the option to do hash-based verification for the downloads. But for every website I checked this functionality is unused:

<hashCheck>ignore</hashCheck>

So this is rather about regular code signing. And code-signed malware isn’t unheard of.

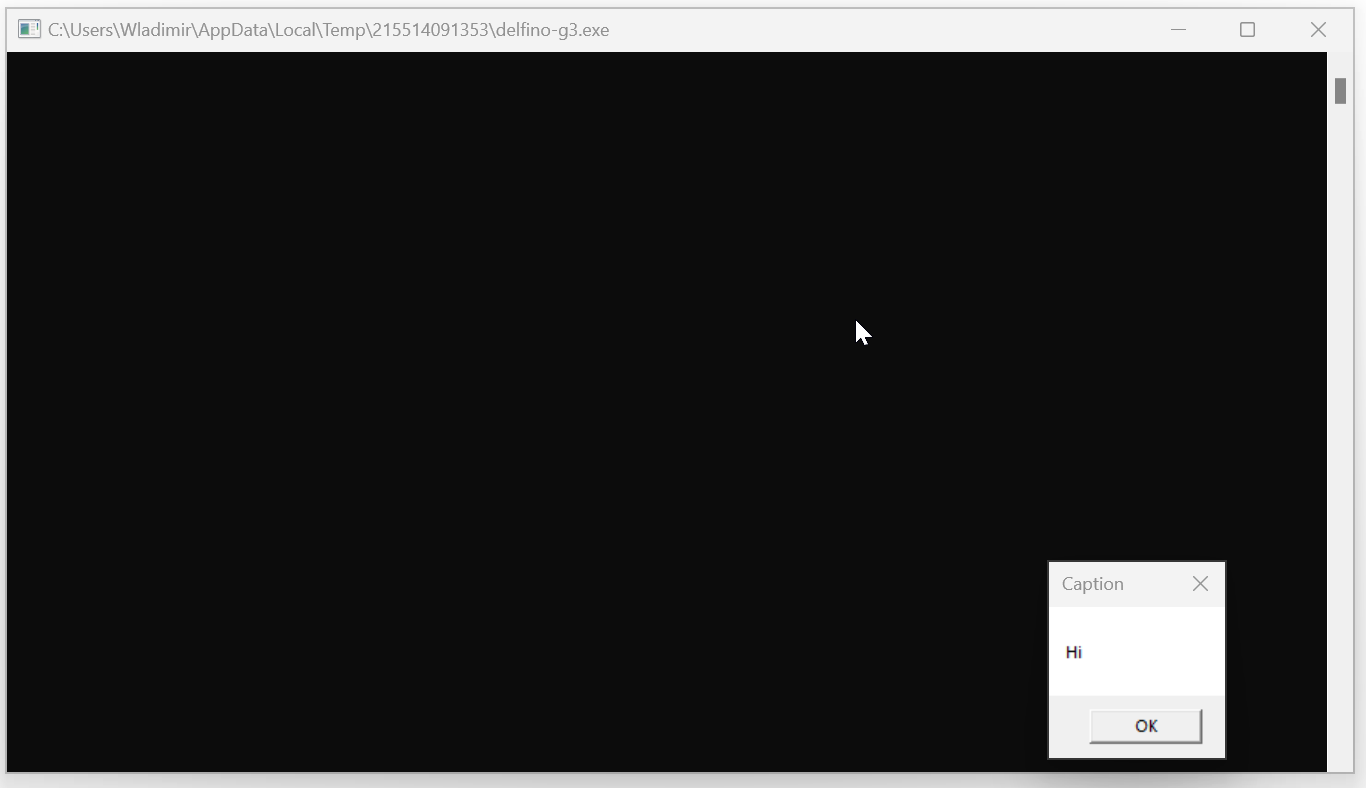

But wait, the signature doesn’t even have to be valid! I tried uploading a self-signed executable to the server. And Veraport allowed this one to run without any complains!

I know, my minimal “malicious” application isn’t very impressive. But real malware would dig deep down into the system at this point. Maybe it would start encrypting files, maybe it would go spying on you, or maybe it would “merely” wait for your next banking session in order to rob you of all your money.

Keep in mind that this application is now running elevated and can change anything in the system. And the user didn’t even have to accept an elevation prompt (one that would warn about the application’s invalid signature) – Veraport itself is running elevated to avoid displaying elevation prompts for each individual installer.

Removing visual clues

Obviously, the user might grow concerned when confronted with a Veraport installation screen out of the blue. Luckily for the attackers, that installation screen is highly configurable.

For example, a malicious website could pass in a configuration like the following:

send_command("getAxInfo", {

"configure": {

"type": "normaldesc",

"addinfourl": "http://malicious.example/addinfo.json",

…

}

});

The addinfo.json file can change names and descriptions for the downloads arbitrarily, making certain that the user doesn’t grow too suspicious:

But manipulating texts isn’t even necessary. The bgurl configuration parameter sets the background image for the entire window. What if this image has the wrong size? Well, Veraport window will be resized accordingly then. And if it is a 1x1 pixel image? Well, invisible window it is. Mission completed: no visual clues.

Information leak: Local applications

One interesting command supported by the Veraport server is checkProcess: give it an application name, and it returns information on the process if this application is currently running. And what does it do if given * as application name?

let processes = send_command("checkProcess", "*");

Well, output of a trivial web page:

That’s definitely a more convenient way of learning what applications the user is running than the complicated search via IPinside.

For security applications, the getPreDownInfo command provides additional information. It will process a policy file and check which applications are already installed. By taking the policy files from multiple websites I got a proof of concept that would check a few dozen different applications:

With this approach producing a version number, it is ideal for malicious websites to prepare their attack: find which outdated security software the user has installed and choose the vulnerabilities to exploit.

Web server vulnerabilities

HTTP Response Splitting

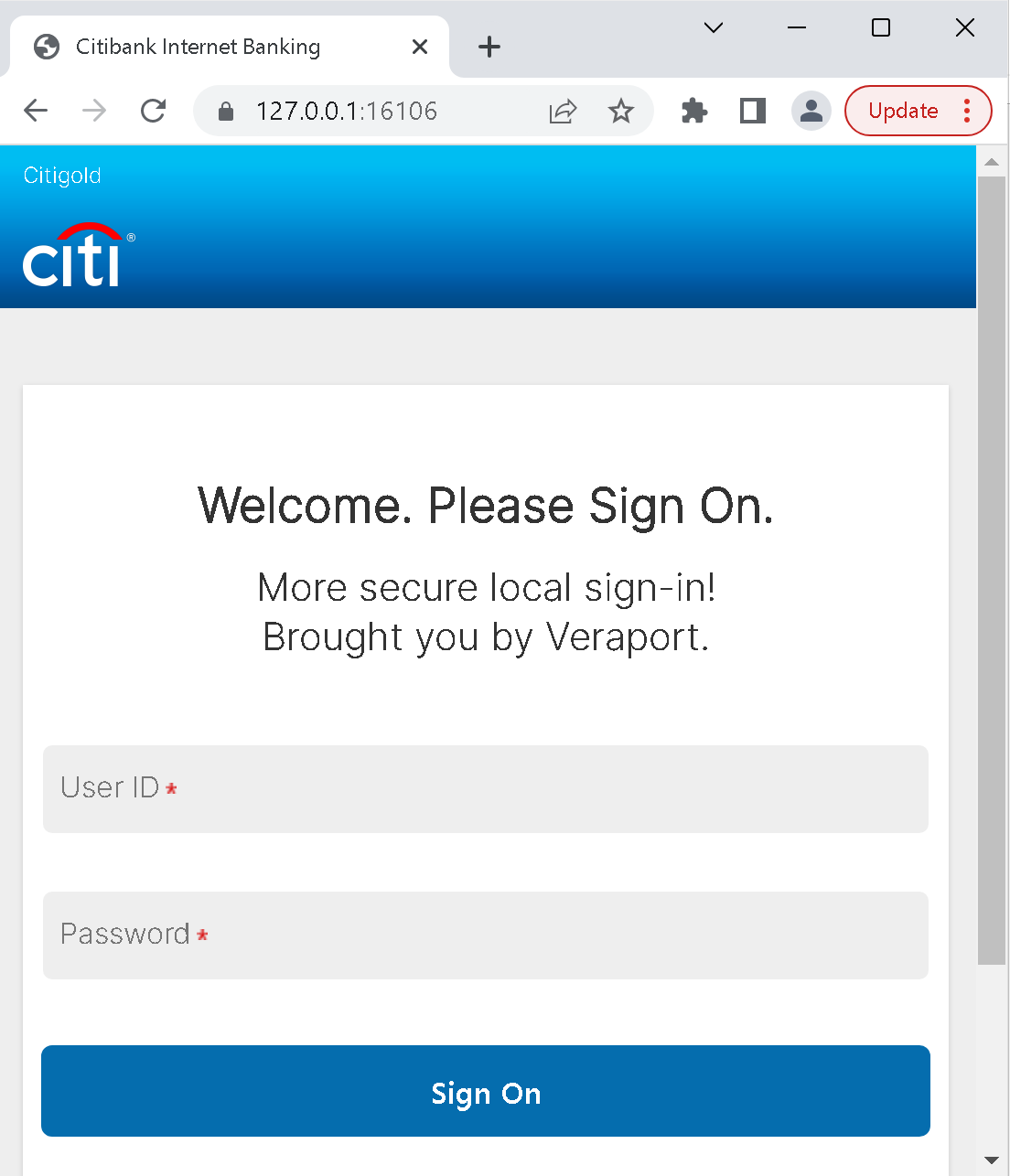

As we’ve seen, Veraport’s local web server under https://127.0.0.1:16106 responds to a number of commands. But it also has a redirect endpoint: https://127.0.0.1:16106/redirect?url=https://example.com/ will redirect you to https://example.com/. No, I don’t know what this is being used for.

Testing this endpoint showed that no validation of the redirect address is being performed. Veraport will even happily accept newline characters in the address, resulting in HTTP Response Splitting, a vulnerability class that has gone almost extinct since all libraries generating HTTP responses started prohibiting newline characters in header names or values. But Veraport isn’t using any such library.

So the request https://127.0.0.1:16106/redirect?url=https://example.com/%0ACookie:%20a=b will result in the response:

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Location: https://example.com/

Cookie: a=b

We’ve successfully injected an HTTP header to set a cookie on 127.0.0.1. And by rendering the Location header invalid, one can even prevent the redirect and serve arbitrary content instead. The request https://127.0.0.1:16106/redirect?url=%0AContent-Type:%20text/html%0A%0A%3Cscript%3Ealert(document.domain)%3C/script%3E will result in the response:

HTTP/1.1 302 Found

Location:

Content-Type: text/html

<script>alert(document.domain)</script>

Google Chrome will in fact run this script in the context of 127.0.0.1, so we have a reflected Cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability here. Mozilla Firefox on the other hand protects against such attacks – content of a 302 response is never rendered.

Persistent XSS via a service worker

Reflected XSS on 127.0.0.1 isn’t very useful to potential attackers. So maybe we can turn it into persistent XSS? That’s possible by installing a service worker.

The hurdles for installing a service worker are intentionally being set very high. Let’s see:

- HTTPS has to be used.

- Code has to be running within the target scope.

- Service worker file needs to use JavaScript MIME type.

- Service worker file has to be within the target scope.

Veraport uses HTTPS for the local web server for some reason, and we’ve already found a way to run code in that context. So the first two conditions are met. As to the other two, it should be possible to use HTTP Response Splitting to get JavaScript code with a valid MIME type. But there is a simpler way.

The Veraport server communicates via JSONP, remember? So the request https://127.0.0.1:16106/?data={}&callback=hi results in a JavaScript file like the following:

hi({"res": 1});

The use of JSONP is discouraged and has been discouraged for a very long time. But if an application needs to use JSONP, it is recommended that it validates the callback name, e.g. only allowing alphanumerics.

Guess what: Veraport performs no such validation. Meaning that a malicious callback name can inject arbitrary code into this JavaScript data. For example, https://127.0.0.1:16106/?data={}&callback=alert(document.domain)// would result in the following JavaScript code:

alert(document.domain)//hi({"res": 1});

And there is the JavaScript file with arbitrary code which can be registered as a service worker. In my proof of concept, the service worker would handle requests to https://127.0.0.1:16106/. It would then serve up a phishing page:

This is what you would see on https://127.0.0.1:16106/ no matter how you came there. A service worker persists and handles requests until it is unregistered or replaced by another service worker, surviving even browser restarts and clearing browser data.

Reporting the issues

I’ve compiled the issues I found into six reports in total. As with other South Korean security applications, I submitted these reports via the KrCERT vulnerability report form.

While this form is generally unreliable and will often produce an error message, this time it straight out rejected to accept the two most important reports. Apparently, something in the text of the reports triggered a web application firewall.

I tried tweaking the text, to no avail. I even compiled a list of words present only in these reports but not in my previous reports, still no luck. In the end, I used the form on December 3rd, 2022 to send in four reports, and asked via email about the remaining two.

Two days later I received a response asking me to submit the issues via email which I immediately did. This response also indicated that my previous reports were received multiple times. Apparently, each time the vulnerability submission form errors out, it actually adds the report to the database and merely fails sending email notifications.

On January 5th, 2023 KrCERT notified me about forwarding my reports to Wizvera – at least the four submitted via the vulnerability form. As to the reports submitted via email, for a while I was unsure whether Wizvera received those as I received no communication on those.

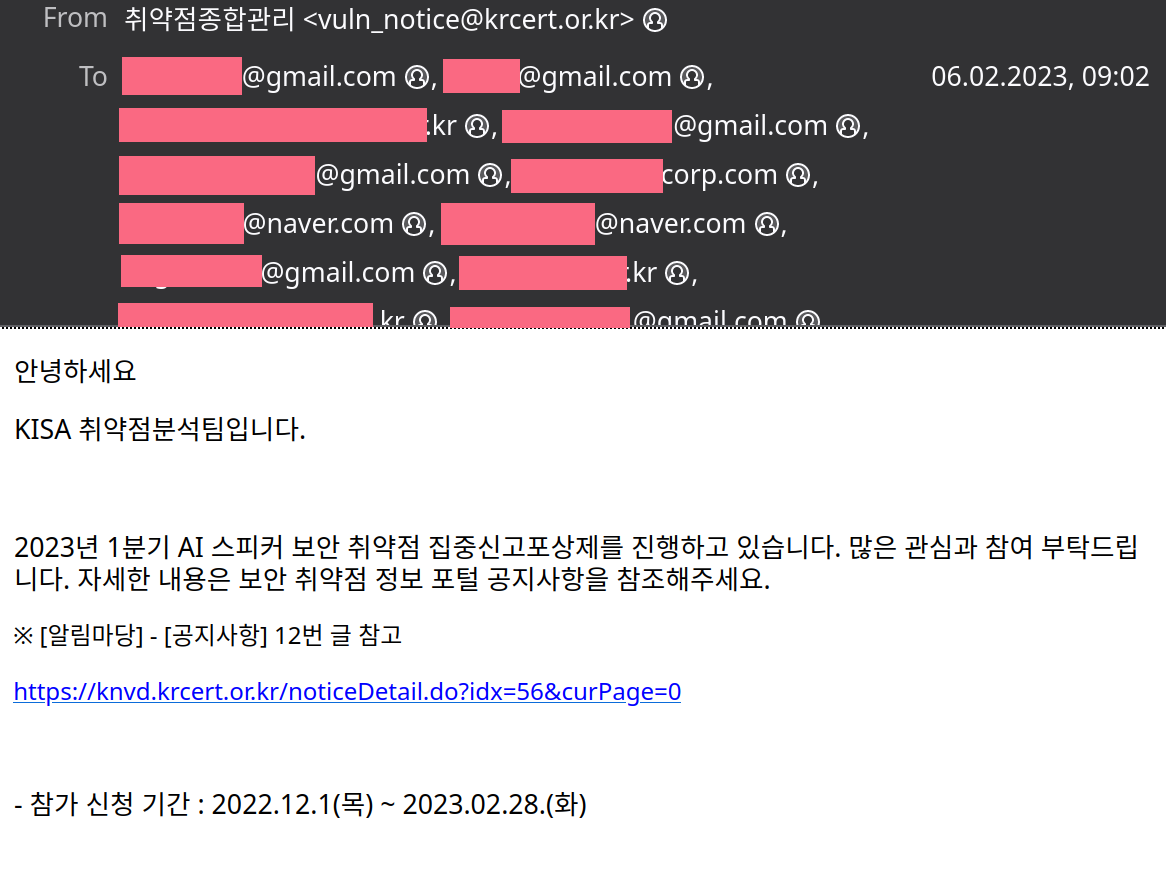

But this wasn’t the last I heard from KrCERT. On February 6th I received an unsolicited email from them inviting me to a bug bounty program:

Yes, the email addresses of all recipients were listed in the “To” field. They leaked the email addresses of 740 security researchers here.

According to the apology email which came two hours later they actually made the same mistake in a second email as well, with a total of 1,490 people affected. This email also suggested a mitigation measure: reporting the incident to KISA, the government agency that KrCERT belongs to.

What is fixed

I did not receive any communication from Wizvera, but I accidentally stumbled upon their download server. And this server had a text file with a full change history. That’s how I learned that Veraport 3.8.6.4 is out:

2864,3864 (2023-01-26) 취약점 수정적용

In my tests, Veraport 3.8.6.4 resolved some issues but not others. In particular, installing a malicious application still worked with a minimal change – one merely had to download the policy via an HTTP rather than an HTTPS connection.

So on February 22 I sent an email to KrCERT asking them to forward my comments to Wizvera, which they did on the same day. As a result, various additional changes have been implemented in Veraport 3.8.6.5 and released on February 28 according to the change history.

Altogether, all the directly exploitable issues seem to have been addressed. In particular, server identity is now being validated for HTTPS connections. Also, Veraport 3.8.6.5 will automatically upgrade HTTP downloads to HTTPS. So untrusted networks can no longer mess with installations.

Window size is no longer determined by the background image, so that the application window can no longer be hidden this way. With Veraport 3.8.6.5 websites also cannot change application descriptions any more.

The redirect endpoint has been removed from Veraport’s local server, and the JSONP endpoint now restricts callback names to a set of allowed characters.

OpenSSL has been updated to version 1.0.2u in Veraport 3.8.6.4 and version 1.1.1t in Veraport 3.8.6.5. The latter is actually current and has no known vulnerabilities.

According to the changelog, JsonCpp 0.10.7 is being used now. While this version has been released in 2016, using newer versions should be impossible as long as the application is being compiled with Visual Studio 2008.

Veraport 3.8.6.5 also addressed the issues mentioned in my blog post on TLS security. The certification authority is being generated during installation now. In addition to that, the application allows communicating on port 16116 without TLS.

Interestingly, I also learned that abusing checkProcess to list running processes is a known issue which has been resolved in 2021 already:

2860, 3860 (2021-10-29)

- checkProcess 가 아무런 결과를 리턴하지 않도록 수정

To my defense: when I tested Veraport, there was no way of telling what the current version was. Even on 2023-03-01, a month after Wizvera presumably notified their customers about a release fixing security issues, only three out of ten websites (chosen by their placement in the Google results) offered the latest Veraport version for download. That didn’t mean that existing users updated, merely that users got this version if they decided to reinstall Veraport. But even by this measure, seven out of ten websites were lagging behind by years.

| Website | Veraport version | Release year |

|---|---|---|

| busanbank.co.kr | 3.8.6.0 | 2021 |

| citibank.co.kr | 3.8.6.4 | 2023 |

| hanacard.co.kr | 3.8.6.1 | 2021 |

| hi.co.kr | 3.8.6.0 | 2021 |

| ibk.co.kr | 3.8.5.1 | 2020 |

| ibki.co.kr | 3.8.6.4 | 2023 |

| koreasmail.co.kr | 2.5.6.1 | 2013 |

| ksfc.co.kr | 3.8.6.1 | 2021 |

| lina.co.kr | 3.8.5.1 | 2020 |

| yuantasavings.co.kr | 3.8.6.4 | 2023 |

Remaining issues

Application signature validation was still broken in Veraport 3.8.6.4. Presumably, that’s still the case in Veraport 3.8.6.5, but verifying is complicated. This is no longer a significant issue since the connection integrity can be trusted now.

While checkProcess is no longer available, the getPreDownInfo command is still accessible in the latest Veraport version. So any website can still see what security applications are installed. Merely the version numbers have been censored and are no longer usable.

It seems that even Veraport 3.8.6.5 still uses the eight years old mongoose 5.5 library for its local web server, this one hasn’t been upgraded.

None of the conceptual issues have been addressed of course, these are far more complicated to solve. Veraport customers still have the power to force installation of arbitrary applications, including outdated and malicious software. And they aren’t restricted to their own website but can sign a policy file for any website.

A compromised signing certificate of a Veraport customer still cannot be revoked, and neither is it possible to revoke a known malicious policy. Finally, the outdated root certificate (1024 bits, MD5) is still present in the application.

Comments

I’m just guessing here, but it might not just be developer laziness. Around that time, new VC++ releases (and their runtimes) started dropping support for old Windows versions tather quickly. If I’m reading this right, VC++2008 is the last Microsoft compiler you can use to target Windows 2000 without resorting to trickery (I think you can still build against MSVCRT.DLL using the WDK?). Not to say anything about the merits of using OS releases that ancient, but to me they sound like a somewhat plausible reason the developers may be stuck with an old compiler version.

Few days ago, North Korea break into some crappy security application Inisafe. And they did actually hacked some government computer.

https://m.hankookilbo.com/News/Read/A2023033010390003530 (Korean Article)

Yes, I’ve seen the news about INISAFE CrossWeb EX being exploited by North Korean hackers. Supposedly, this happened last year already, before I even started this article series.

As expected, there is trouble distributing the update which fixes the vulnerability. According to https://www.ddaily.co.kr/news/article/?no=260579, only 40% of the companies implemented the patched version a month after it was released. Which probably means that the patched version is on their websites, not that it has been installed by any users. As I said here:

Quite some mess…